Living with others: How household size and family bonds relate to happiness

Key insights

- For most people in the world, family relationships are an important source of happiness. This chapter explores how the size and configuration of households – where most family interactions take place – are associated with people’s happiness.

- A household size of about four members is predictive of higher happiness levels. People in these households enjoy abundant and very satisfactory relationships.

- People who live on their own often experience lower levels of happiness, primarily due to lower levels of relational satisfaction. People in very large households can also experience less happiness, probably linked to diminished economic satisfaction.

- Governments should consider how economic policies may have secondary effects on relationships, hence affecting the wellbeing in families. National statistical offices should prioritise the development of metrics that assess the quantity and quality of interpersonal relationships and the bonds that underpin them.

- Latin American societies, characterised by larger household sizes and strong family bonds, offer valuable lessons for other societies that seek higher and sustainable wellbeing.

Introduction

Caring and sharing – sustained by warm, close, and enduring relational bonds – are crucial to human happiness.[1] In particular, family bonds promote lasting relationships, and households provide a context where these bonds develop and, in many cases, thrive.[2] Thus, the field of wellbeing science should pay more attention to household configurations and intra-household relationships.

This chapter examines the relationship between happiness, household size, and family configuration. We make extensive use of the rich data provided by INEGI, the National Statistical Office of Mexico, through its ENBIARE 2021 survey, as well as additional information from Colombia. Our analyses contrast the situation in Mexico with that of European countries, drawing on data from the European Social Survey 2020.

We hypothesise that a small number of household members may limit affective connections, which negatively impacts happiness, while a large number of members may impose economic burdens that also threaten wellbeing. Consequently, the chapter explores the potential existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between life satisfaction and the number of household members. An in-depth analysis of satisfaction across different life domains suggests that the number of household members is associated with certain economic costs but also offers broad relational benefits, such as increased satisfaction with affective life, family, and personal relationships.[3]

We also investigate the association between life satisfaction and various family configurations. The findings indicate that these configurations significantly influence happiness. For example, two-parent households are associated with higher levels of life satisfaction among adult members, while adults living in single-person and single-parent households tend to experience lower levels of happiness. The presence of additional family members in single-parent households appears to mitigate some of the negative effects of single-parenthood on happiness.

Literature review

The family as a central relational space

Happiness is nurtured in relational spaces and the family is at the heart of these connections.[4] Caring and sharing are practices that inherently rely on the presence of and interaction with others, beginning with family members. The family is where people first learn to care for and share with others, creating the foundation for broader social interactions and for wellbeing.[5] The family works as a reference for how people interact with others in their life.[6] Families are associated with close, warm, and genuine relationships that last for long stretches in people’s journey in life.

Wellbeing researchers have recently been encouraged to adopt a systemic perspective,[7] which has roots in psychology since the late 1950s, particularly in family therapy and family studies.[8] Systemic approaches assert that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts and that emergent phenomena arise between people who are in relationships, rather than from out-of-context individuals. This perspective examines how a family’s structure and dynamics influence its members, recognising that people exist within an emotional ecosystem where family bonds shape identity and wellbeing. It emphasises that happiness is not solely individual enjoyment but the shared joy and caring experienced within relationships.[9]

Research on subjective wellbeing often emphasises social cohesion, community involvement, and prosocial behaviours within broader civic spaces, but the family’s foundational role in shaping these behaviours is frequently overlooked. By acknowledging the influence of family dynamics on prosocial development, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of how to enhance wellbeing in societies. Before civic engagement and charitable activities appear, the family is the space where people start to build interpersonal relationships.

From a sociological perspective, a family may be conceived as a social unit or group of people who are related by blood, marriage, adoption, or other long-term commitments who typically live together and share economic, emotional, and social activities.[10] From a psychological perspective, families are understood in terms of caring, sharing gratifying activities, and nurturing and supporting their members which foster a sense of belonging and identity that significantly contributes to people’s wellbeing.[11] This perspective emphasises emotional bonds, interpersonal dynamics within the family, and the shared joys and challenges in life.[12]

Families and households

Families and households are different both conceptually and empirically. On the one hand, the concept of family tends to emphasise kinship ties, socialisation, social roles, nurturing, and the transmission of culture and values across generations. On the other hand, a household commonly refers to a group of people, regardless of their type of relationship, who live together in the same dwelling and share living arrangements. A household may consist of one person who lives alone, persons who are not related, or several people with family bonds. In most cases, households are constituted based on family ties.

Household size and configuration are commonly determined by the number of children and the type of coresident family group.[13] Household size and its possible configurations are important for the family dynamics that may emerge from them, including those relating to caring and sharing practices and their relationship with happiness.

Household size, family configurations, and happiness

Mexican data shows the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between life satisfaction and the number of people in a household.[14] In Colombia, the heads of households, spouses in two-parent households, and especially those who are married, work, and have medium-sized families (four persons), report the highest levels of happiness.[15] Convergent results have been found in Mexico where university students from two-parent households show greater levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction than those living in single-parent households.[16] The impact of family configuration on wellbeing points to the importance of the quality of interpersonal relationships that are established and developed in families. In particular, relationships based on affection, close communication, repeated contact, and mutual support are a source of family satisfaction and, in turn, life satisfaction as a whole.[17]

Research on the relationship between family configuration, household size, and wellbeing offers insights that are relevant to the analyses in this chapter. First, the size and configuration of families and the dynamics within them are not innocuous, they affect the happiness of their members. This is particularly true for marriage bonds,[18] parenthood bonds,[19] and the number of family members.[20] Second, there are family characteristics, such as the presence of one or two parents, that have a particularly significant effect on the wellbeing of family members. Third, life satisfaction is related to the contextual circumstances of the family – such as the material living conditions and the family’s life cycle – and to specific characteristics of the parents or heads of household (age, education, etc.). All these factors are interrelated and it is not always easy to disentangle their links and their effects on wellbeing.

While family relationships have historically been viewed as traditional sources of support,[21] it is also important to highlight the emotional depth and sense of value in family relationships. They are rooted in mutual affection and companionship that transcend mere supportive roles and imply person-based relationships, where people know each other well and where the purpose of the relationship is the relationship itself. This kind of relationship is central to the joint enjoyment of life.[22] The intrinsic value of such relationships lies in the warmth, closeness, and genuine affection that family members share with each other over long periods of time. Hence, family relationships are valued not only for what they provide but, fundamentally, for the quality of the emotional and meaningful bonds involved. The abundance and quality of family relationships contribute to people’s happiness and we expect household size and configuration to contribute to both the quantity and quality of family relationships.[23]

Relationships based on affection, close communication, repeated contact, and mutual support are a source of family satisfaction and, in turn, life satisfaction as a whole.

Household characteristics in Latin America and Europe

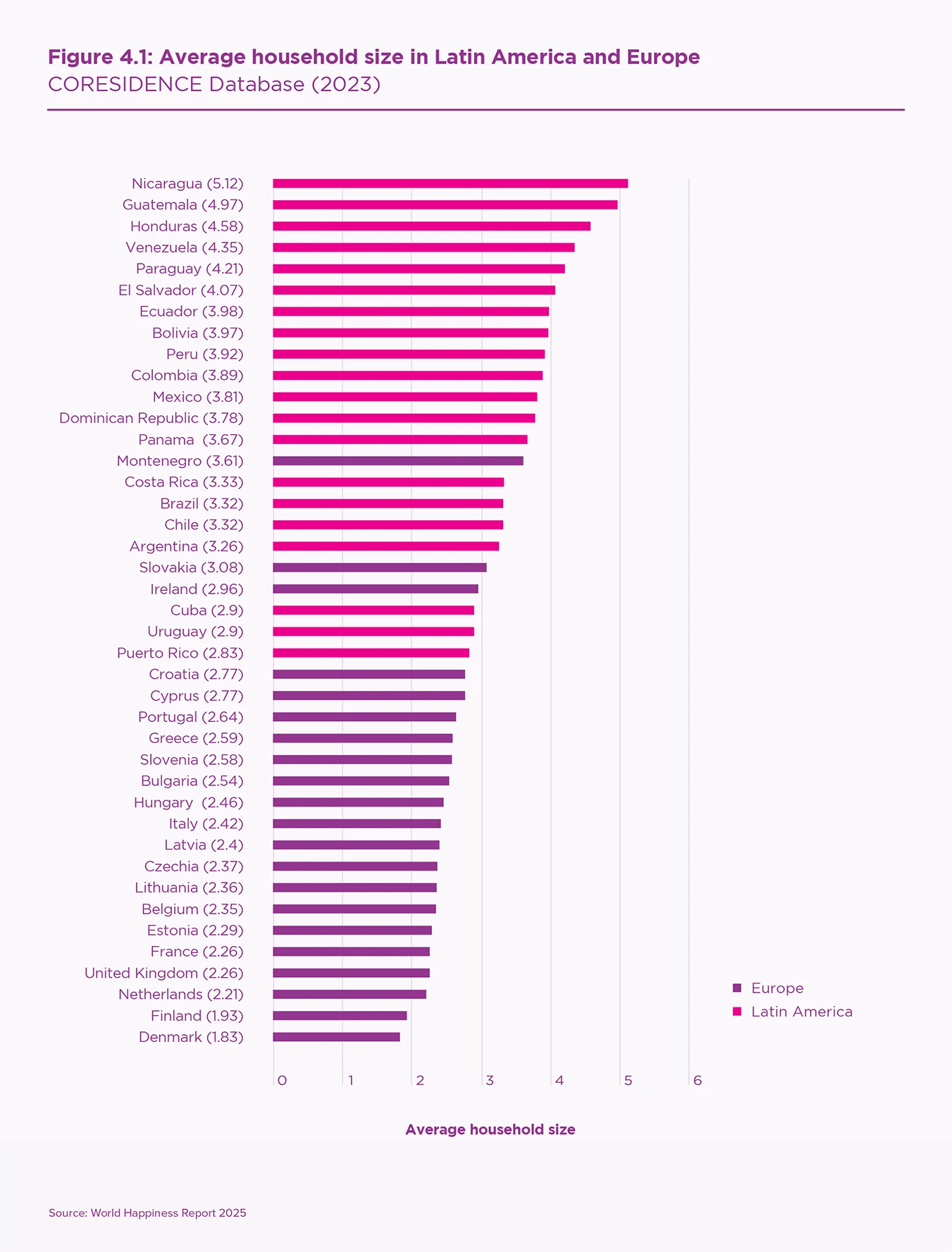

We now turn to the specific and contrasting characteristics of households in Latin America and Europe. Figure 4.1 presents the average household size for many Latin American and European countries taken from the CORESIDENCE Database.[24] Substantial differences are observed between the two regions. Except for Cuba, Uruguay, and Puerto Rico, the average household size in Latin America exceeds three people per household, a size only reached in two European countries: Montenegro and Slovakia. The average household size exceeds five in Nicaragua and it is fewer than two in Finland and Denmark.

Linear thinking may suggest that living alone may be better than living with others, even if it’s more expensive. However, this view leaves aside the value of interpersonal relationships, which are an important source of wellbeing and are fostered by sharing the same house with other people that we care about.[25]

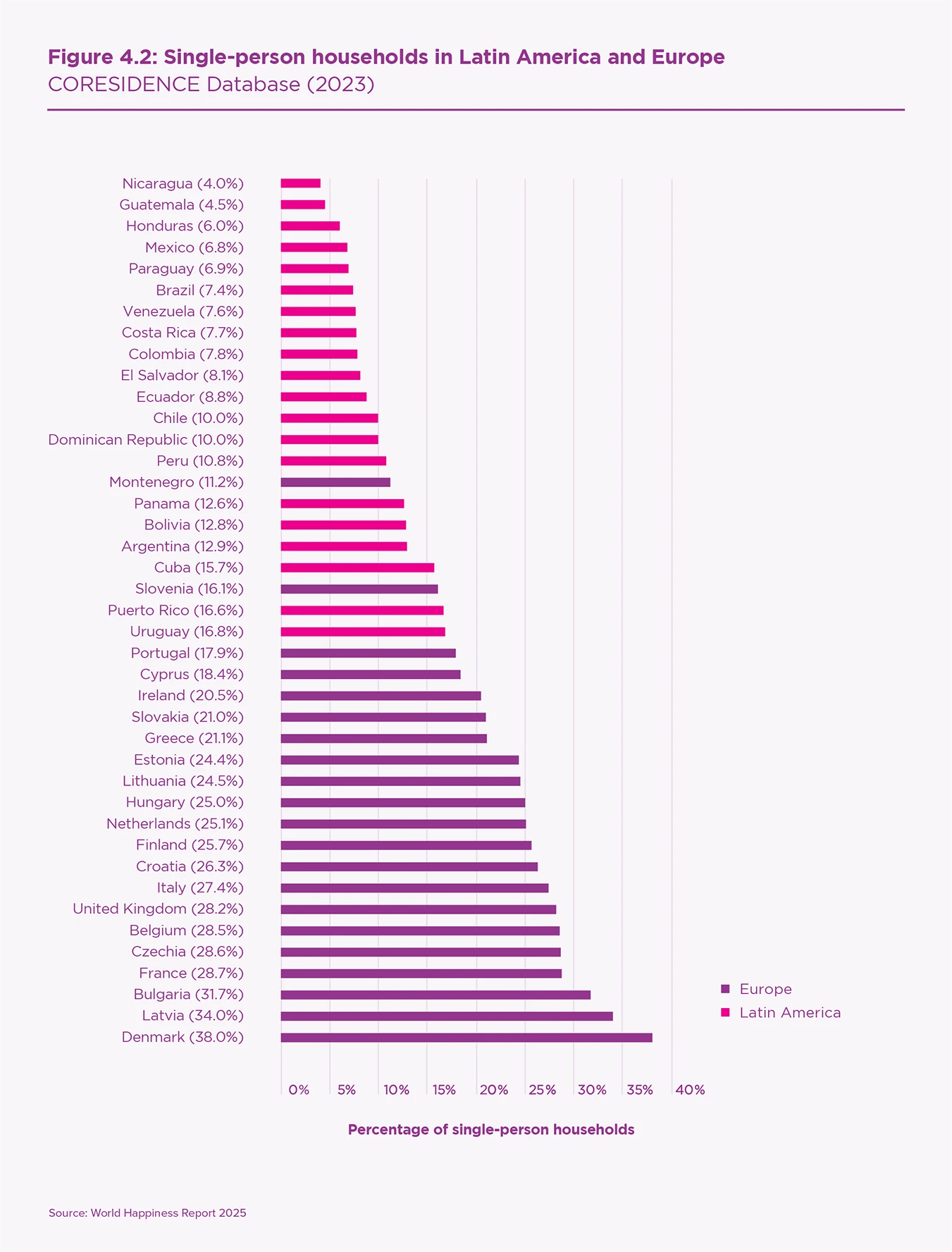

Figure 4.2 shows the proportion of single-person households in Latin American and European countries. The proportion ranges from 4% in Nicaragua to 38% in Denmark.

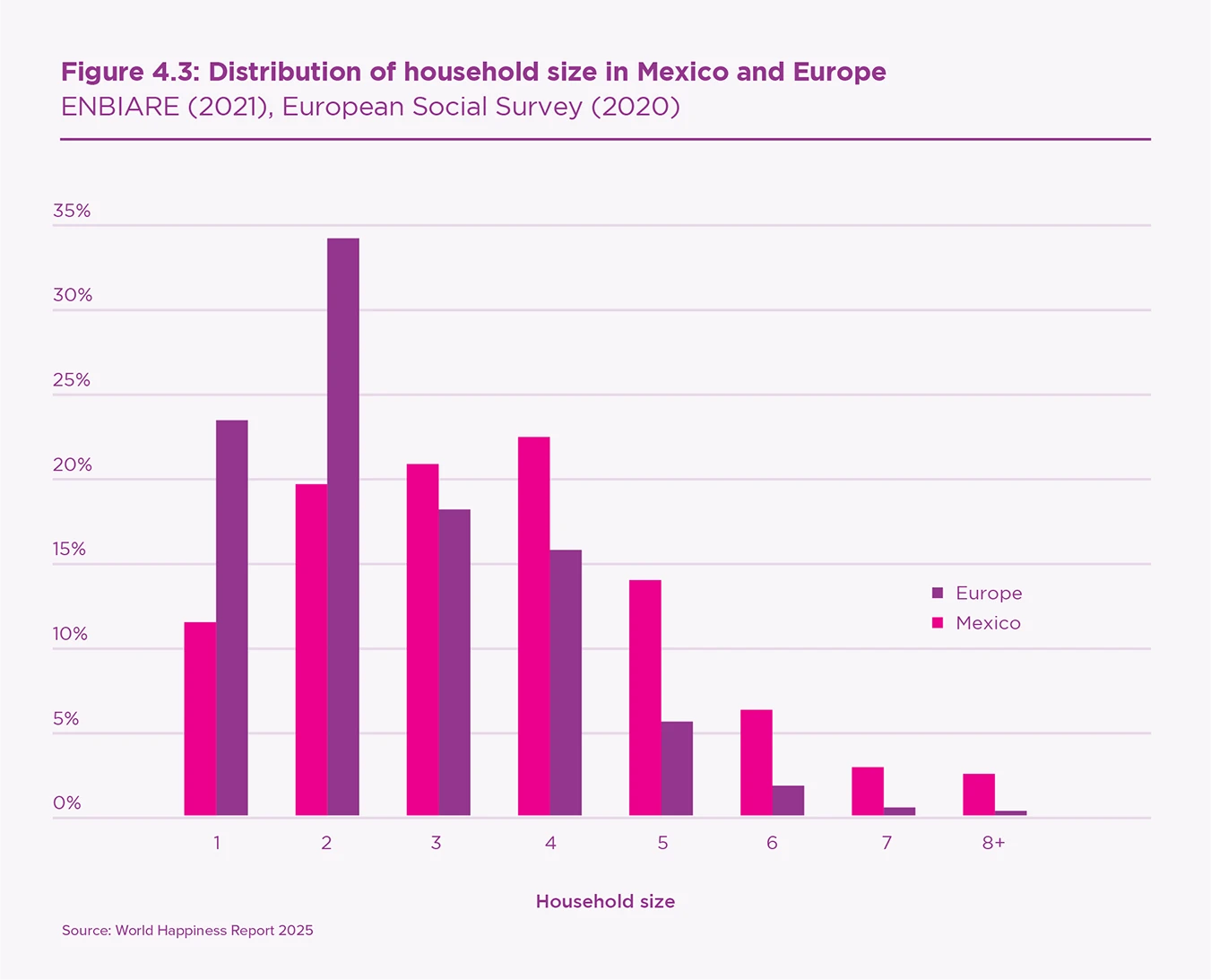

In Figure 4.3, we compare the distribution of household size between Mexico and European countries. We observe that single-person households make up 23% of European households, but that figure is only 11% in Mexico. In addition, households with two members comprise 34% of European households and less than 20% in Mexico. Thus, 55% of households in Europe have two members or fewer, but this figure is about 30% in Mexico. Furthermore, almost half of Mexican households include four people or more, while this figure is about 24% for Europe. Mexico is economically poorer than the average European country. However, larger households imply a potential advantage to build positive social interactions within the household, which could partially counterbalance the differences in income with Europe. This is one of several plausible explanations for why most Latin American countries report higher wellbeing than predicted by their GDP per capita.

Box 4.1: Trends in family configurations

Over the past 50 years, the composition of families and households worldwide has undergone significant change.[26] The emerging trends raise significant concerns from a wellbeing perspective as they suggest increasing threats to both the quantity and quality of person-based relationships and the role that households play in contributing to happiness. It is unclear if economic growth can adequately compensate for these detrimental effects.

Some of the most relevant trends are:

- Decrease in family size: Between 1970 and 2020, the majority of households have decreased by approximately 0.5 persons per decade on average.[27] This global trend is largely explained by the reduction in the number of children. Fertility rates across the globe have halved, from 4.84 in 1950 to 2.23 in 2021.[28]

- Rise in single-person households: They are becoming widespread in Europe and are growing rapidly in Latin America, but they are still rare in Africa and most Asian countries.[29] Single-person households range from 2.6% in Cambodia to 38% in Switzerland.

- Rise in single-parent families: Since the 1990s, single-mother households have been on the rise in all developing regions, while single-father households have remained stable.[30]

- In many parts of the world, population aging has led to more multigenerational households, in which elderly parents live with their adult children and grandchildren. This change is particularly prevalent in regions and social sectors where economic restrictions and cultural norms favour family care for the young and old.[31]

- More people are choosing to live without children. Couples without children are prevalent in OECD countries, ranging from 15% in Poland and Slovenia to 26% in Canada. In the United States, couples without children (25%) are slightly more prevalent than couples with children (24%).[32]

The relationship between household size and happiness

Descriptive statistics of household size

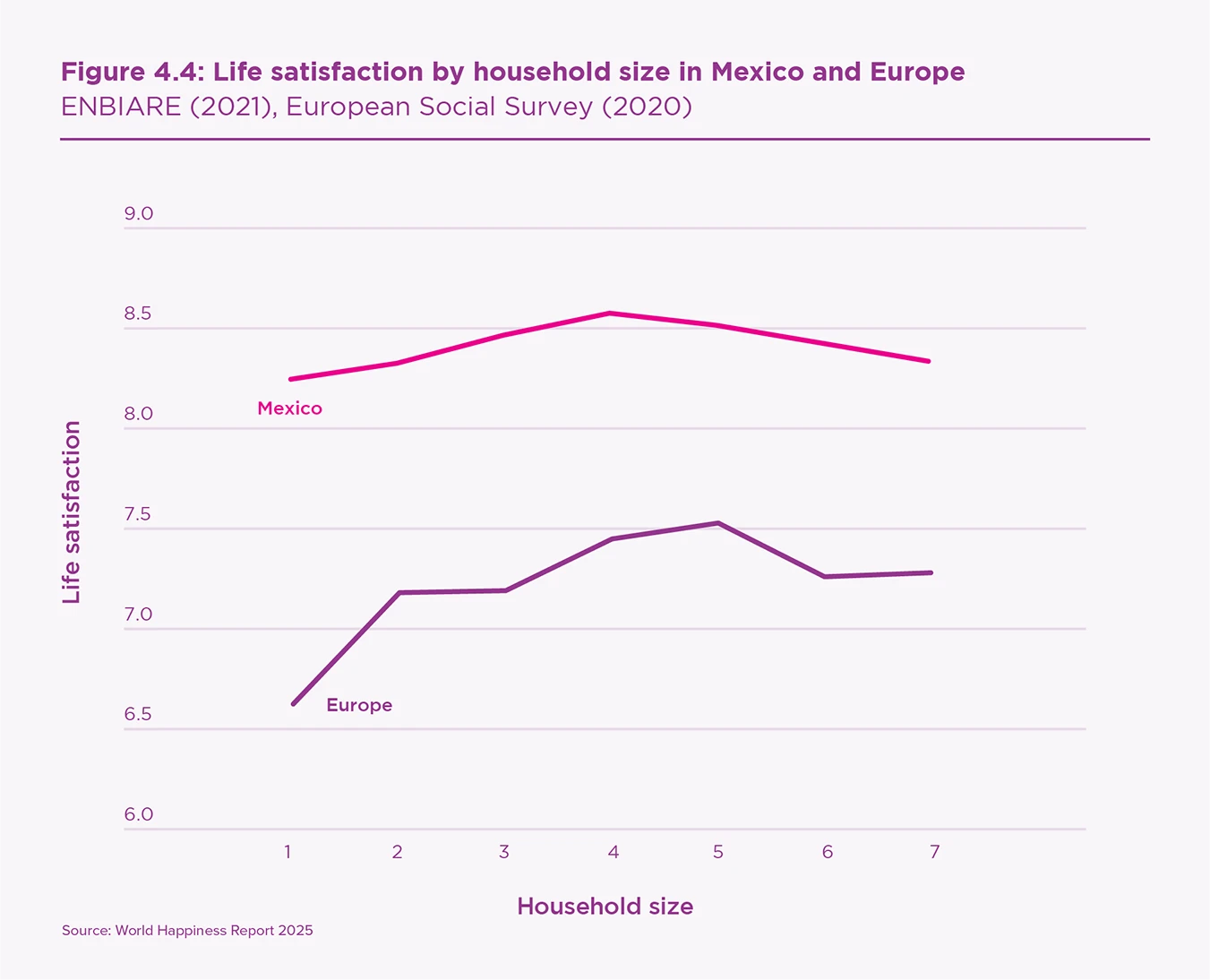

What is the relationship between household size and happiness? This is the first empirical question we tackle in this chapter. We use surveys from Mexico, Colombia, and several European countries to address this question, taking advantage of the data available in Mexico to deepen our understanding of the relationship between life satisfaction and household size. Figure 4.4 presents average life satisfaction by the number of members in the household for both Mexico and Europe (note that these figures differ from the rankings in Chapter 2 as they come from different data sources).[33] Our objective is to analyse how life satisfaction varies with the number of household members in each region, rather than comparing the regions directly.

In both Mexico and Europe, the highest average life satisfaction is reported by people who live in households with four to five members. We also observe an inverted U-shaped relationship. Average life satisfaction is lower for people in single-person households as well as households with six or seven members. In Europe, there is a high wellbeing cost for people in single-person households. While the average life satisfaction reaches 7.5 for people in households with five members, it is only 6.6 for people in single-person households. We should not forget that almost 24% of households in Europe are single-person. The wellbeing cost for people in single-person households is also observed in Mexico, but to a lesser degree than in Europe. It seems that living in single-person households has a wellbeing cost, but it depends on the context so this cost varies across regions. For example, it may not be the same to live in a single-person household when you have close relatives in the neighbourhood or good friendship ties.[34]

Statistical analysis of household size

We ran regression analyses to delve deeper into the relationship between household size and life satisfaction in Mexico, taking socio-economic and demographic characteristics into account. The regression specification is flexible enough to test the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship. The statistical findings are presented in Table 4.1 in the online appendix.[35] It is worth noting that the coefficients for the number of household members are statistically significant, although the goodness of fit of the entire model is low, suggesting that it would be very risky to predict the life satisfaction of a particular person from their information on assets, education, gender, age, and number of members in the household.[36]

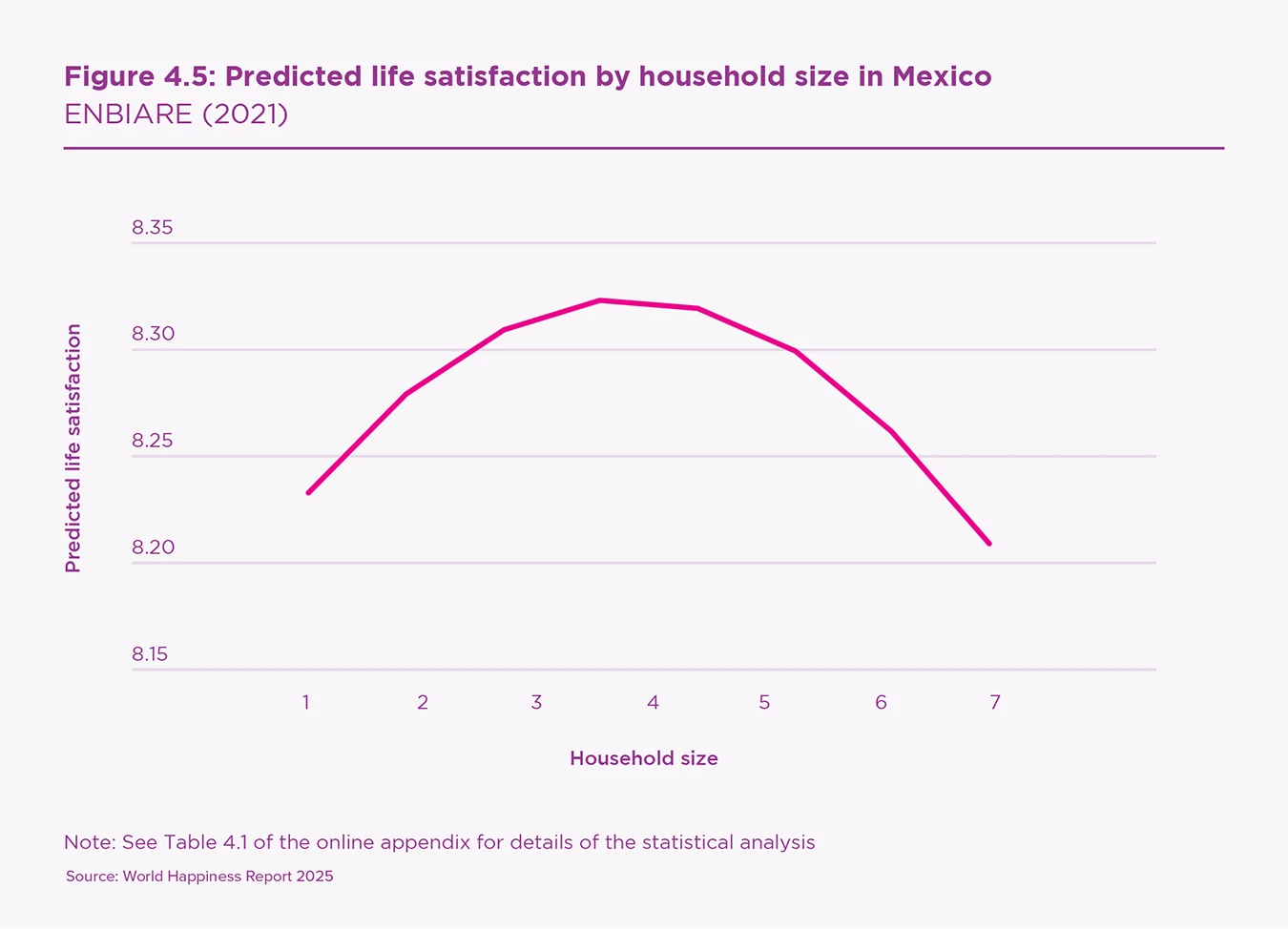

Figure 4.5 presents the predicted life satisfaction for different household sizes based on the estimated coefficients presented in Table 4.1. The predicted value is computed for a woman with average age, education, and assets, and an inverted U-shaped relationship is confirmed. We estimate that the highest life satisfaction is reached in households of 4 to 5 members, keeping socio-economic and demographic characteristics constant.[37] This figure is higher than the average household size in Mexico, which is 3.5. Therefore, from a wellbeing perspective, the current average household size in Mexico is suboptimal.

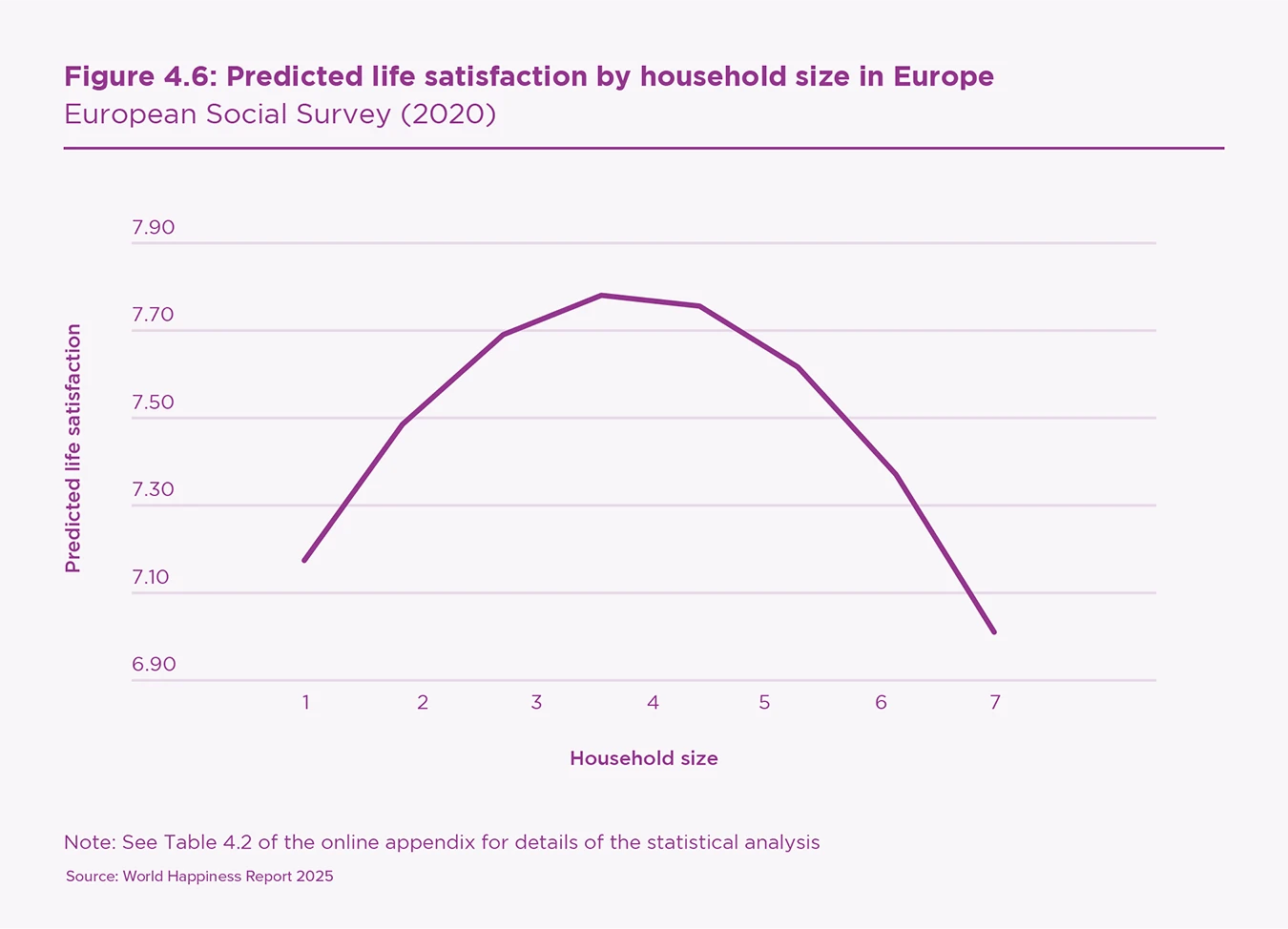

We conducted similar regression analyses for the European region using data from the European Social Survey. Table 4.2 in the online appendix presents the estimated coefficients for two models.[38] Figure 4.6 presents the predicted life satisfaction for different household sizes based on a woman with average age, education, income, and living in Belgium.

Figure 4.6 uses the estimated coefficients for the model that incorporates more countries and observations. Again, we observe an inverted U-shaped relationship, regardless of the estimated model. The highest life satisfaction is achieved with a household size of four members, well above the current average for European households which is 2.5. Therefore, from a wellbeing perspective, the current average household size in European countries seems to be suboptimal too.

This analysis shows two important results for both Mexico and Europe. First, the current average size of households is below the size associated with the highest predicted level of life satisfaction for adults within the region. Second, people who live in single-person or very large households tend to report lower wellbeing. The reasons for suboptimal household size are not addressed in this chapter. A deeper understanding of the inverted U-shaped relationship is obtained by studying how satisfaction in different life domains relates to household size.

Domains-of-life explanation for the inverted U-shaped relationship

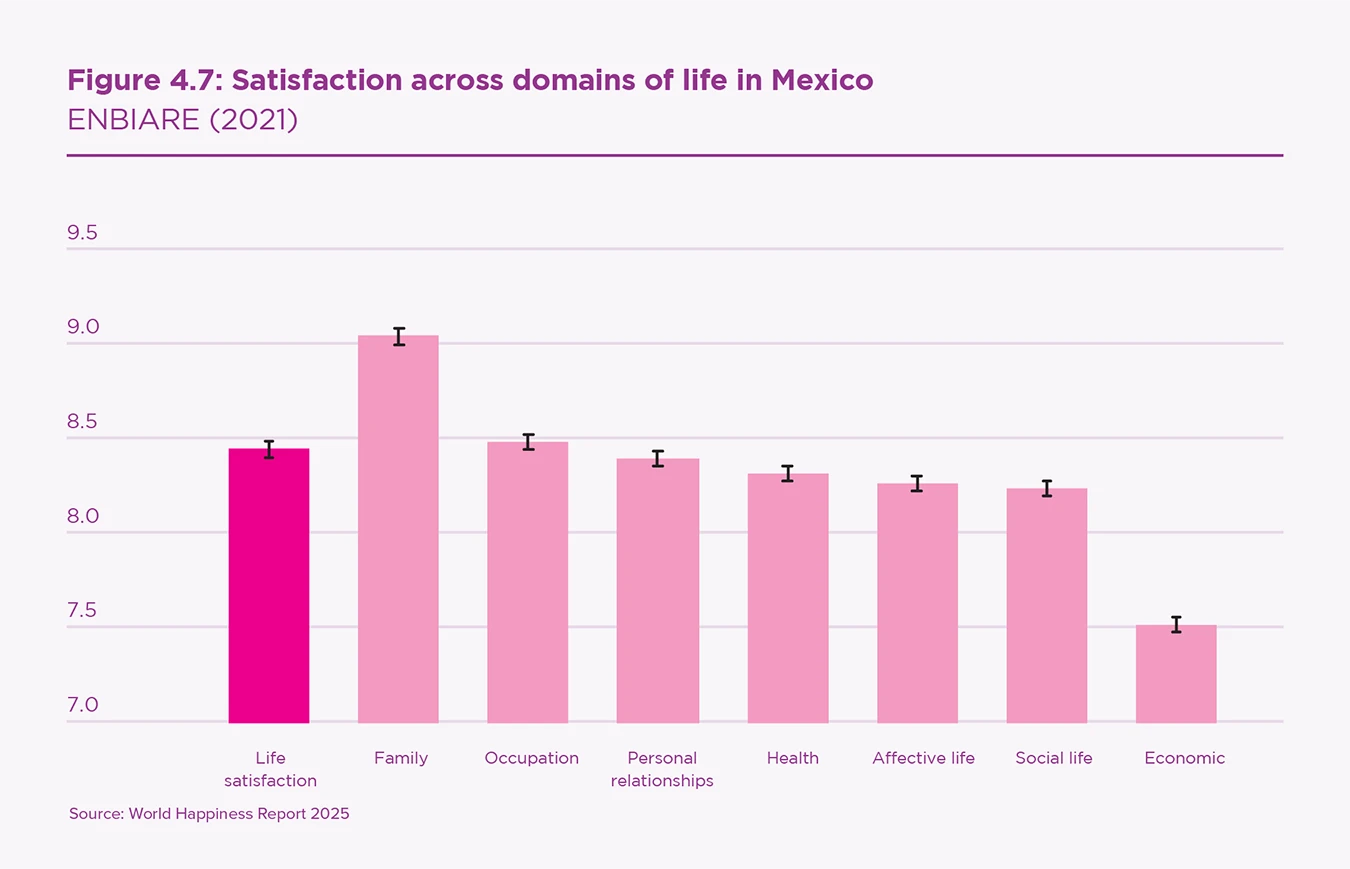

The domains-of-life approach understands life satisfaction as emerging from satisfaction in specific realms of life.[39] The Mexican ENBIARE survey asks people about their satisfaction in several domains of life. Here, we consider seven domains: personal relationships, social life, affective life, family, economic situation, health, and occupational situation. The first four domains are clearly relational. Figure 4.7 shows average satisfaction by domain of life. We observe that satisfaction with family life is quite high in Mexico, with an average satisfaction above 9, on a scale ranging from 0 (totally unsatisfied) to 10 (totally satisfied). Satisfaction with the economic situation is relatively low.

How is household size related to satisfaction in these different domains of life?[40] Figure 4.8 presents the predicted satisfaction in each domain for different household sizes, based on the estimated coefficients presented in Table 4.3 in the online appendix. The predicted satisfaction is computed for a woman with sample average age, education, and assets.

The key insight portrayed by Figure 4.8 is in the relational domains. An inverted U-shaped relationship is observed in family satisfaction, where maximum family satisfaction would be reached with a household size of about six members. This suggests that there are substantial benefits from living in large households in terms of family satisfaction. The same situation is observed for satisfaction with affective life, where maximum satisfaction is reached for about five to six household members. Similarly, for the domain of personal relationships, maximum satisfaction is reached with household members close to five.

These results suggest there are relational benefits associated with living in households between four and six members, which is well above the average household size for Mexico of 3.5 members. Recent research[41] shows that, to a certain degree, the size of the household contributes to generating quality relationships which may be associated with greater satisfaction with personal relationships, affective life, and family. There is also evidence that the main variable explaining family satisfaction is its relational foundation and, in particular, its affective component, more so than economic factors.[42] Thus, the life satisfaction gains from living in large households seem to be associated with the important relational benefits associated with large households.

Our empirical analysis also shows that economic satisfaction is inversely associated with the number of household members. This finding suggests that the number of members in the household implies an economic burden that reduces economic satisfaction, possibly signalling that the benefits from material resources have to be distributed among a greater number of household members as household size increases.

The findings presented in Figure 4.8 (and in Table 4.3) pose a dilemma: small households – and even single-person households – tend to report higher levels of economic satisfaction. However, small households report lower satisfaction with their interpersonal relationships. If economic satisfaction is prioritised, then a small household size offers advantages. However, people are much more than mere consumers and their human relationships play a central role in their lives and their wellbeing.

Household configuration and life satisfaction

Households are relational spaces and the different types of family bonds within the household may influence the nature of relationships and, in consequence, the life satisfaction of household members. This section focuses on the nature of family bonds within households and how they are associated with life satisfaction.[43]

We consider six basic household configurations in the following analyses:

The number of households inhabited by two or more people with no family ties at all is negligible so they are not considered in this analysis. All six configurations involve some type of family bond and we examine the life satisfaction reported by adults who live in one of these household configurations and were selected to respond to the ENBIARE or European Social Survey.

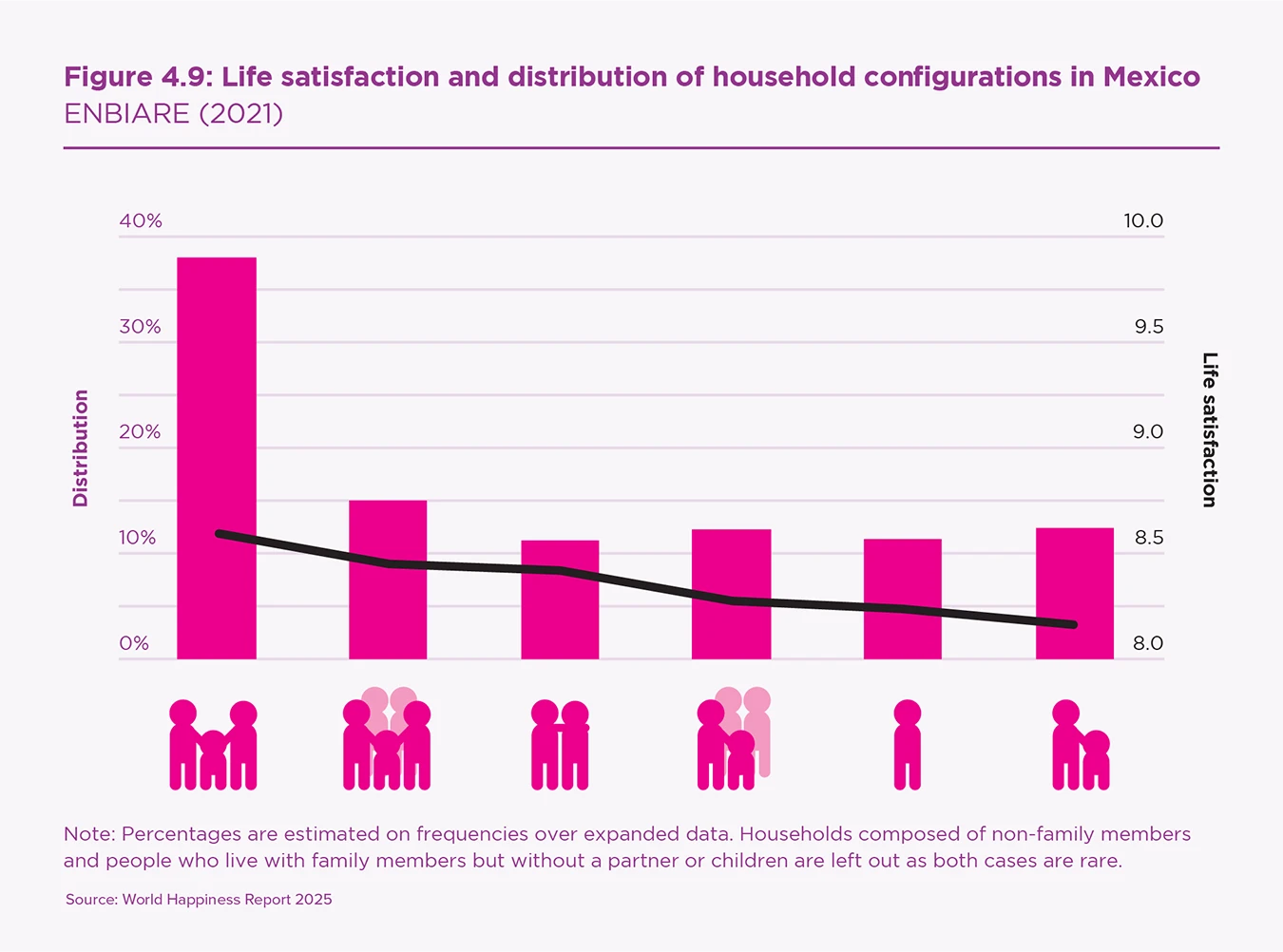

Descriptive statistics of household configuration (Mexico)

In Figure 4.9, we present the distribution of the Mexican population by household configuration and the average life satisfaction associated with each configuration. Couples with at least one child are the most frequent household configuration in Mexico, representing almost 38% of households in the country. People in this type of household report the highest life satisfaction with an average of 8.6. Life satisfaction is also relatively high for those who live in households of couples without children and for those who live in households with a couple, children, and other relatives. In these cases, the average life satisfaction is around 8.4. Life satisfaction is relatively low for people who live in single-person households, in single-parent households with children, and in single-parent households with children and other relatives. The presence of extended family has a favourable effect for single parents with children but seems to be detrimental for couples with children.

These results suggest that households based around couples report the highest levels of life satisfaction. This high level of life satisfaction, combined with a high percentage of these household configurations, clearly contributes to increased life satisfaction in Mexico. This is a wellbeing driver that is not frequently considered in the happiness literature.

Statistical analysis of household configuration (Mexico)

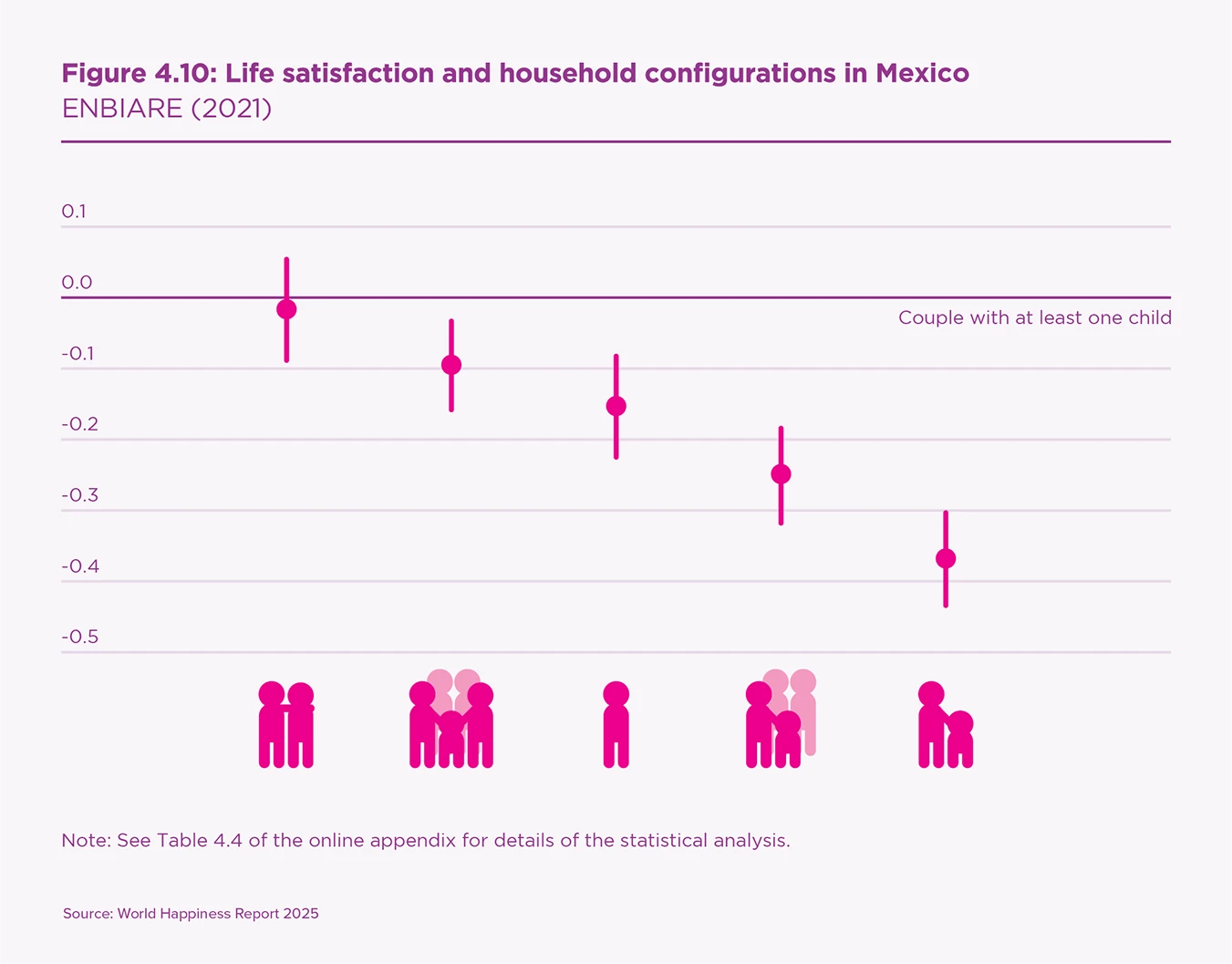

We ran regression analyses to study the association between life satisfaction and family configurations further. The analysis controls by age, age squared, gender, and educational level of the interviewee, as well as by assets in the household (as a proxy for the household’s economic situation). Table 4.4 in the online appendix presents the estimated coefficients. The category of reference corresponds to a couple with at least one child.

Figure 4.10 shows the relevant estimated coefficients. The lowest levels of life satisfaction are associated with single-person and single-parent households. We also observe significantly lower life satisfaction among single-parent households, even after adjusting for the economic situation of the household. However, this observation is for single-parent households where there are no other family members, which suggests that the presence of other relatives can mitigate the wellbeing cost for people who live in single-parent households. Couples without children report levels of life satisfaction that are statistically similar to people who live in couples with children.[44]

Domains-of-life explanation (Mexico)

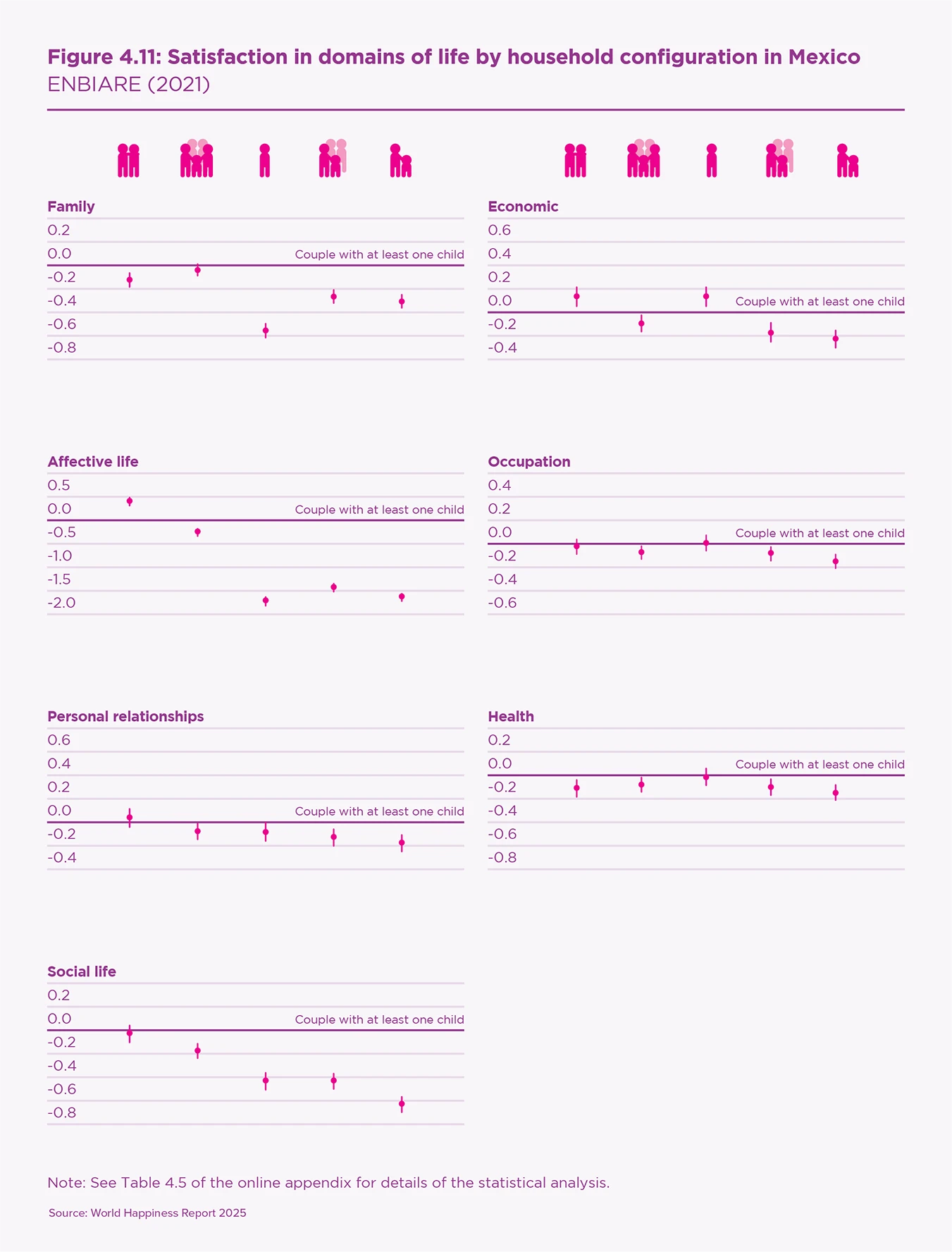

The domains-of-life approach allows us to delve into the origin of the wellbeing costs associated with single-person and single-parent households. We ran regression analyses to study the association of satisfaction in each domain of life with family configurations, controlling by age, age squared, gender, education level, and assets in the household. Table 4.5 in the online appendix shows the estimated coefficients from the quantitative analyses.

The relevant estimates are presented in Figure 4.11. In comparison to people living in a couple with at least one child, people living in single-person households report lower satisfaction in their personal relationships, affective life, and family life. They also report higher economic satisfaction but this is not enough to compensate for lower satisfaction in relational domains. This explains the lower life satisfaction reported by people in single-person households seen in Figure 4.10.

Compared to couples with children, people who live in couples without children have greater economic and affective satisfaction, but lower satisfaction with health and family. Overall, their life satisfaction is no different than people who live in couples with children.

People living in couples with children and other relatives report lower life satisfaction than people living in couples with children. This lower life satisfaction is explained by lower satisfaction in almost all the domains of life that were studied.

People who live in single-parent households (with or without other relatives) report lower life satisfaction than couples with children and they have lower satisfaction in all the domains of life under consideration. It is important to note that people in single-parent households with other relatives report greater life satisfaction than people in single-parent households with no relatives. This is mostly explained by their greater satisfaction with affective life and personal relationships.

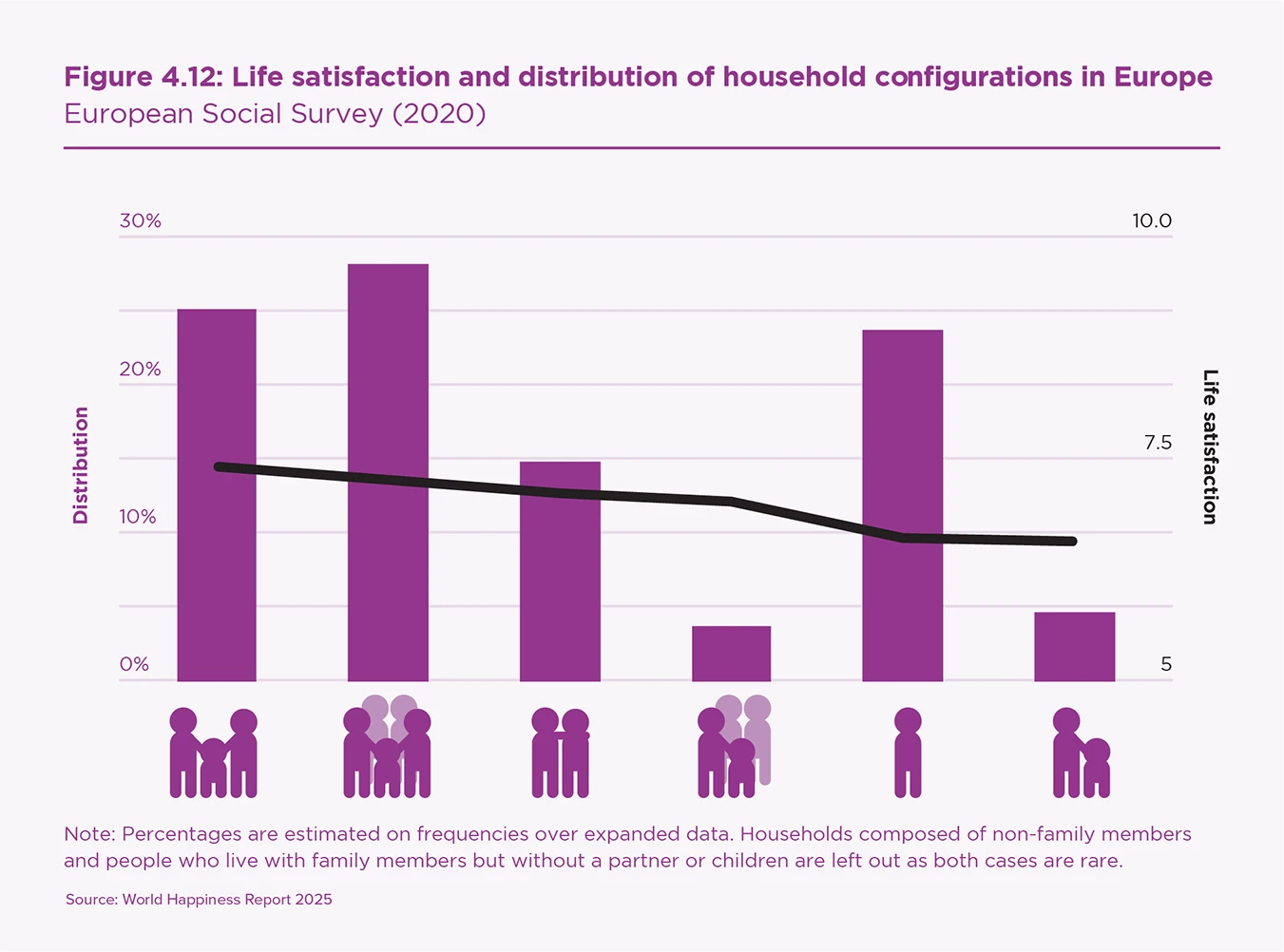

Descriptive statistics of household configuration (Europe)

The distribution of household configurations in European countries (Figure 4.12) differs from Mexico (Figure 4.9). The percentage of single-person households in Europe (24%) is more than double the number in Mexico (11%). The situation is similar for couples without children, 28% for Europe and 11% for Mexico. Couples with children represent 25% of households in Europe, while in Mexico it reaches almost 38%. Couples with children and other relatives are less than 4% of households in Europe, while this figure is almost 15% in Mexico. The percentage of single-parent households is relatively small in Europe (5%) compared to Mexico (12%), while the percentage of single-parent households with other relatives is slightly higher in Europe (15%) than in Mexico (12%).

As we saw in Mexico, there is a life satisfaction cost for single-person households. A similar situation is observed for single-parent households with no other relatives. Couples, with or without children, enjoy the highest level of life satisfaction.

The difference in life satisfaction between people who live in couples with children and people living alone is much smaller in Mexico than in Europe (a decline of 0.37 in Mexico vs. a decline of 0.84 in Europe). In addition, there is a higher percentage of people living alone in Europe. This combination of factors – the high cost of living in single-person households and the large percentage of households in this category – is clearly detrimental to the life satisfaction of Europeans.[45]

Statistical analysis of household configuration (Europe)

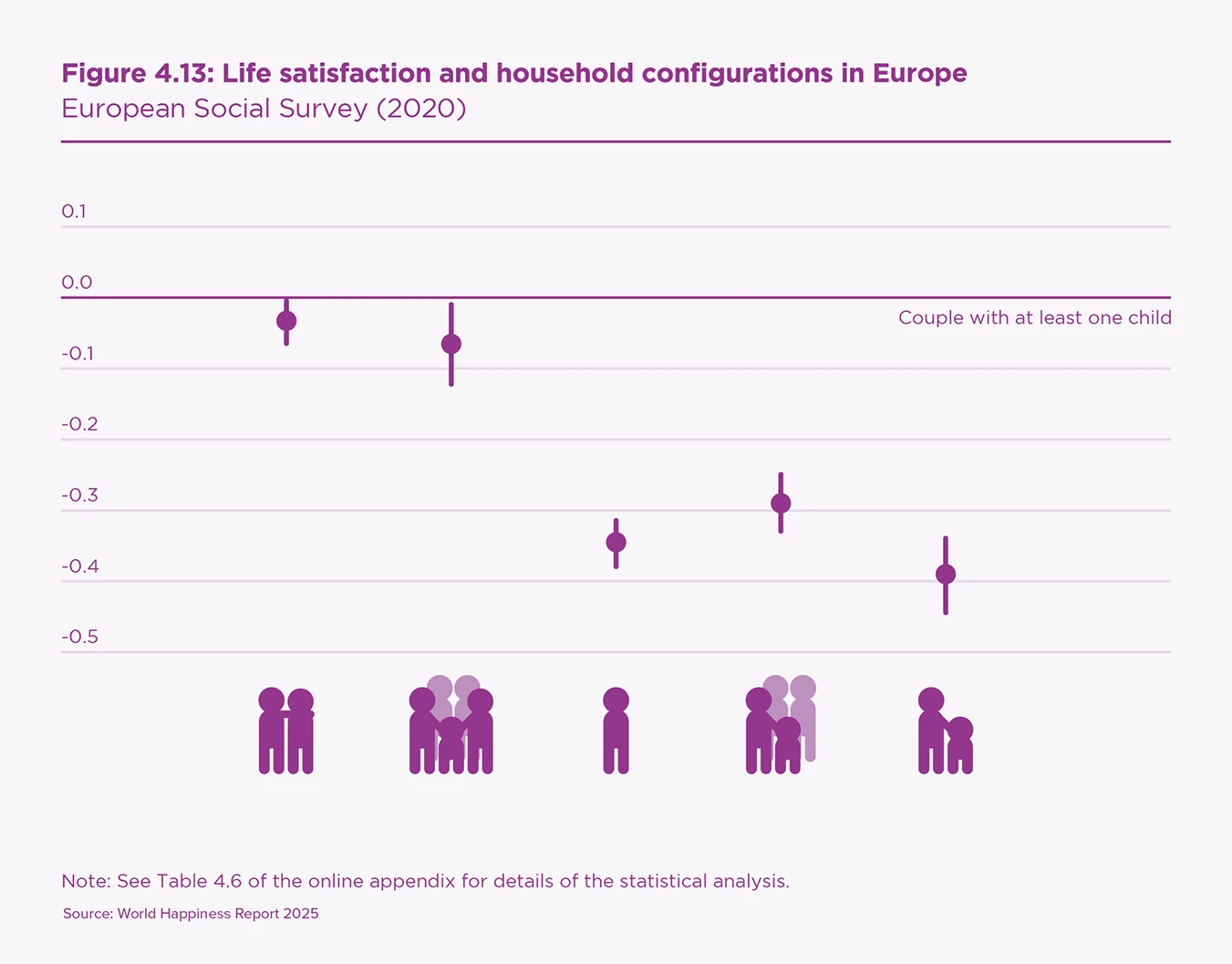

We ran regression analyses for European countries using data from the European Social Survey. The analysis studies the relationship between life satisfaction and household configurations and controls by age, age squared, gender, education level, and country fixed effects. Table 4.6 in the online appendix presents the estimated coefficients.

Figure 4.13 shows the relevant coefficients for household configurations in Europe. Similarly to Mexico, people living in single-person and single-parent households have lower life satisfaction than people who live in couples with children. However, this cost is larger in Europe than in Mexico. Contextual factors such as the role of extended family and friendships may explain this difference. People who live in couples with children and other relatives also have lower life satisfaction than couples with children and no other relatives. People who live in single-parent households with other relatives have greater life satisfaction than single parents who live with no other relatives. In general, the life satisfaction pattern across household configurations is very similar in Mexico and Europe.

Final considerations

The size and configuration of households are highly relevant for people’s wellbeing. The household is not only a dwelling. It is a space for coexistence that favours the emergence of high-quality relationships which may significantly contribute to life satisfaction. The study of households often emphasises economies of scale in the use of resources as well as specialisation in the division of labour. However, the wellbeing benefits of living together in households are not limited to economic aspects.

Households are relational spaces – a community of caring and sharing – where members create strong interpersonal relationships that contribute to their life satisfaction. Households of two or more people frequently foster close, genuine, and long-lasting relationships, with subsequent benefits for life satisfaction.

In this chapter, we show that household size and configuration are statistically associated with life satisfaction in Mexico and Europe. We find that people who live on their own report lower levels of life satisfaction, and this is not associated with economic reasons.

In this chapter, we show that household size and configuration are statistically associated with life satisfaction in Mexico and Europe. We find that people who live on their own report lower levels of life satisfaction, and this is not associated with economic reasons. On the contrary, single-person households report greater economic satisfaction but lower life satisfaction due to relational deprivation. Controlling for economic resources, this effect is smaller in Mexico than in Europe, which suggests that the wellbeing cost experienced by those who live on their own may be context dependent. Presumably, higher average levels of income may help to hide the relatively larger cost of loneliness to people’s wellbeing.

We present evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between household size and life satisfaction. A household of around four people has the highest life satisfaction in both Mexico and Europe. Information from Latin American countries indicate that the quantity (i.e., time spent with family members) and quality (i.e., sharing emotions, manifesting affection, communicating, and giving support when facing challenges) of family relationships is positively associated with household size. We also find that people who live in single-parent households report lower life satisfaction. This is mostly explained by their lower satisfaction in relational domains of life, as well as their lower economic satisfaction.

Further analyses indicate that the relationship between household size and life satisfaction is influenced by the extent to which family members engage in caring and sharing activities.[46] Thus, the time spent together as a family, along with positive emotional exchanges, affective bonds, genuine interest, communication, and mutual support largely accounts for the positive link between household size and life satisfaction. Additional analyses also indicate that household size is positively associated with access to support.[47] This allows us to conclude that, at least in part, the association between household size and life satisfaction is mediated by the relevance of household size on caring and sharing activities.

Household configurations differ across regions, countries, and decades. Due to these differences, and because household configurations matter for people’s wellbeing, researchers should take these differences into account when contrasting life satisfaction between countries and across time. It is also important to consider these differences even when contrasting the wellbeing of people living in the same country, as their household configuration may vary.

Globalisation and the geographical relocation of production impose considerable strain on the social fabric, destabilising families and weakening familial and social bonds.

Some prevailing social trends are detrimental to the kinds of household configurations that promote life satisfaction. Indeed, these trends are often linked to the erosion of relational spaces. Such trends are intricately tied to economic policies and development strategies that have, in recent decades, prioritised economic growth while neglecting the vital role of family relationships and broader social connections.

These policies aim at economic targets such as investment, exports, and infrastructure development, yet their consequences extend well beyond the economic sphere, often being inadequately acknowledged. For instance, globalisation and the geographical relocation of production impose considerable strain on the social fabric, destabilising families and weakening familial and social bonds. The reallocation of resources is frequently linked to heightened job insecurity which, in turn, can undermine the quality of family relationships. Moreover, the deregulation of labour markets and capital movements, while attracting foreign investment, can also exacerbate job vulnerability and disrupt work-life balance. Similarly, an educational focus on enhancing human capital, while crucial for productivity, may overlook the development of socio-emotional skills that are essential for fostering positive social interaction.

In this context, social policy has often been conceived as a palliative measure, designed to address the social problems generated or, at best, not sufficiently addressed by pro-growth policies. It is within the realm of social policy to introduce pro-family initiatives, albeit as a reactive measure rather than as part of a proactive strategy. Specific pro-family policies, such as initiatives to improve work-life balance, promote gender equity, and provide maternity or childcare benefits, attempt to mitigate some of the familial challenges that negatively impact wellbeing. However, these policies are far less effective when implemented within a broader and hostile socio-economic context. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a more comprehensive reassessment of economic policies – one that recognises the critical importance of family relationships for overall wellbeing.

Ultimately, societal progress should not be measured by income levels, but rather by the wellbeing experienced by its members. A more holistic approach to policy-making, which acknowledges the relevance of relations and family bonds as a core element of prosperity, is essential for fostering sustainable, long-term wellbeing.

Box 4.2: Family, the social fabric, and the crisis of violence in Ciudad Juárez

At the beginning of the 21st century, Ciudad Juárez, a Mexican city on the border with the United States, suffered from an acute crisis of violence to the point that, with 229 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2008, it was considered “the most violent city in the world”.[48] With only 1% of the country’s population, Ciudad Juárez concentrated 28% of the total homicides committed in Mexico. At the same time, it’s youth were victims and participants in an enormous escalation of violence that included organised crime, robberies, kidnappings, ‘rent’ collection, homicides, femicides, and serious problems of domestic violence and child abuse.

This crisis resulted from the confluence of multiple factors, one of which was the deterioration of family relationships and community life. This was a city that based its growth on the export maquiladora industry, whose viability demanded that large volumes of the working population migrate from other parts of the country. Those who came to work in Ciudad Juárez were mostly poorly educated and did not have the traditional family support networks that they left in their places of origin. They lacked various social services (e.g., institutional support for care activities) which encouraged their children to grow up without adequate guardianship and with emotional deficiencies that made them more vulnerable to being co-opted by criminal gangs.

This situation coincided with several demographic characteristics of Ciudad Juárez, in relative terms, such as high frequency of working women, single mothers, absent fathers, both parents working, smaller households, and more homes made up of people without family ties. The growth model followed in Ciudad Juárez focused on the conditioning of the town for the proper functioning of businesses without considering the many aspects involved in a more humane model of development. Hence, there was not an effective policy for promoting healthy family relationships nor proper institutional and community development programs that could counterbalance the tendencies towards the deterioration of the social fabric.[49]

Perhaps because of the deeply socio-relational origin of the problem, police actions to address it were ineffective. It was not until the authorities adopted an holistic approach to rebuild the social fabric through community work and social participation that the crisis was contained and reversed.[50] This approach focused on education, culture and sports, the construction or rehabilitation of public spaces, physical and mental health services, social security protection, support for local businesses, and attention to addictions among many other initiatives.

All this highlights the importance of maintaining healthy social ties so that economic and community progress can be sustained in the long run. Likewise, it shows there are links between family, community, public safety and economic spheres, that leaders must be very attentive to. In turn, this implies that statistical monitoring should not be limited to material progress. It should also monitor indicators of subjective wellbeing, with a focus on the quality of family and social ties. Specifically, it is a reminder to national statistical offices around the world of the importance of systematically tracking these types of variables and communicating them in a timely and relevant way to citizens and policy makers.

References

Aknin, L. B., Broesch, T., Hamlin, J. K., & Van de Vondervoort, J. W. (2015). Prosocial behavior leads to happiness in a small-scale rural society. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(4), 788–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000082

Baarck, J., d’Hombres, B., & Tintori, G. (2022). Loneliness in Europe before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy, 126(11), 1124–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.09.002

Barraza, L., et. al. (2009). Diagnóstico sobre la realidad social, económica y cultural de los entornos locales para el diseño de intervenciones en materia de prevención y erradicación de la violencia en la región norte: el caso de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Comisión Nacional para Prevenir y Erradicar la Violencia contra las Mujeres, Secretaría de Gobernación, Gobierno de México. http://www.conavim.gob.mx/work/models/CONAVIM/Resource/pdf/JUAREZ.pdf

Barrera, M. (1986). Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 413-445.

Barrera, M. Jr., Sandler, I. N., & Ramsey, T. B. (1981). Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies on college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9, 435-447.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L.M. (1991) Attachments Styles Among Young Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226-244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

Beavin Bavelas, (2021). Pragmatic of Human Communication 50 years later. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 40(2), 3–25.

Bengtson, V.L. (2001). Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x

Beytía, P. (2016) The singularity of Latin American patterns of happiness. In: M. Rojas (ed) Handbook of Happiness Research in Latin America. (17-29) Springer.

Beytía, P. (2017) Vínculos Familiares: Una Clave Explicativa De La Felicidad. In: Reyes, C. & Muñoz, M., La familia en tiempos de cambio. Santiago: Ediciones UC. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3089321

Botha, F., & Booysen, F. (2014). Family functioning and life satisfaction and happiness in South African households. Social Indicators Research. 119(1), 163-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0485-6

Brown, Roy I., & Brown, I. (2014) Family Quality of Life. In A. Michalos (ed) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Wellbeing Research. (2194-2201). Springer Reference.

Bhattacharjee, N. V., Schumacher, A. E., Aali, A., Abate, Y. H., Abbasgholizadeh, R., Abbasian, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd ElHafeez, S., Abd-Elsalam, S., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahifar, M.-A., Abdoun, M., Abdullahi, A., Abebe, M., Abebe, S. S., Abiodun, O., Abolhassani, H., Abolmaali, M., … Vollset, S. E. (2024). Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet, 403(10440), 2057–2099. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00550-6

Cohen, P. N. (2021). The Rise of One-Person Households. Socius, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211062315

Cohn, D., Horowitz, J., & Arditi, T. (2022) Financial Issues Top the List of Reasons U.S. Adults Live in Multigenerational Homes. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/03/PSDT_03.24.22_multigenerationalhouseholds.report.pdf (Retrieved: August 2024).

Diener M. L., & Diener, M. B. (2008) What makes people happy? A Developmental Approach to the Literature on Family Relationships and Wellbeing. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (eds) The Sciences of Subjective Wellbeing. (347-375). The Guilford Press. NY.

El Economista (2009) Juárez, la ciudad más violenta del mundo. August, 26. https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Juarez-la-ciudad-mas-violenta-del-mundo-20090826-0102.html

Esteve, A., Pohl, M., Becca, F., Fang, H., Galeano, J., García-Román, J., Reher, D., Trias-Prats, R., & Turu, A. (2024) A global perspective on household size and composition, 1970–2020. Genus 80, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-024-00211-6

Esteve, A., Galeano, J., Turu, A., García-Román, J., Becca, F., Fang, H., Pohl, M. L. C., & Trias Prat, R. (2023). The CORESIDENCE Database: National and Subnational Data on Household and Living Arrangements Around the World, 1964-2021 [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8142652

European Social Survey (2020) European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure Consortium. Round 10. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/

Florenzano, R., & Dussaillant, F. (2011) Felicidad, salud mental y vida familiar. In M. Rojas (coord) La medición del progreso y del bienestar. Propuestas desde América Latina (247-257). Foro Consultivo Científico y Tecnológico.

Gobierno Federal, Gobierno de Chihuahua, & Gobierno Municipal de Juárez (2010) Estrategia Todos somos Juárez. Reconstruyamos la Ciudad. https://www.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sep1/Resource/889/2/images/todossomosjuarezb(1).pdf

INEGI (2021) Encuesta Nacional de Bienestar Autorreportado (ENBIARE). México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enbiare/2021/

Inkeles, A., & Smith, D. H. (1976). Becoming modern: Individual change in six developing countries (2. print). Harvard Univ. Press.

Inglehart, R. (2010). Faith and freedom: Traditional and modern ways to happiness. In E. Diener, J.F. Helliwell, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), International Differences in Well-Being. (pp. 351-397) Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural Evolution, Cambridge University Press.

Leyva, G. (2014) Los hogares pequeños viven mejor… ¿o no? Coyuntura Demográfica, Num. 6, July, 21-27.

Lomas, T., Waters, L., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Kern, M. L. (2021). Third wave positive psychology: Broadening towards complexity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(5), 660-674. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501

McHale, S., Crouter, A., & Whiteman, S. (2003). The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development, 12(1), 125-148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00225

Millán, R, & Esteinou, R. (2021). Satisfacción familiar en América Latina: ¿importan las relaciones? Perfiles Latinoamericanos, 29(58), 1-12. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.18504/pl2958-012-2021

Montoya, B. I., & Landero, R. (2008) Satisfacción con la vida y autoestima en jóvenes de familias monoparentales y biparentales. Psicología y Salud, 18(1), 117-122.

Moyano, E. & Ramos, N. (2007) Bienestar subjetivo: midiendo satisfacción vital, felicidad y salud en población chilena de la región del Maule. Universum. Revista de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, 2(22), 184-200, Universidad de Talca, Chile, http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=65027764012.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846-895. doi: 10.1037/a0035444.

Newman, L., Arthur, L., Staples, K., & Woodrow, C. (2016). Recognition of Family Engagement in Young Children’s Literacy Learning. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 41(1), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911604100110

Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). Parenthood and well‐being: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 198-223.

OECD (2013), OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Wellbeing, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en.

OECD (2016) OECD Family Database. Social Policy Division, Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

Oliva, E. & Villa, V.J. (2014) Hacia un concepto interdisciplinario de la familia en la globalización. Justicia Juris. 10(1), 11-20. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S1692-85712014000100002\&lng=en\&tlng=es.

Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2024). Loneliness and Social Connections. One World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/social-connections-and-loneliness#loneliness-solitude-and-social-isolation (retrieved: August 3rd, 2024).

Rojas, M. (2006) Communitarian versus individualistic arrangements in the family: What and whose income matters for happiness? In Estes., R. (ed.) Advancing Quality of Life in a Turbulent World, Springer, 153-167.

Rojas, M. (2018). Happiness in Latin America has social foundations. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (eds.) World Happiness Report 2018 (pp. 114–145). London: Springer.

Rojas, M. (2024) The joint enjoyment of life. explaining high happiness in Latin America. Journal of Happiness Studies 25, 100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00817-9

Rojas, M., Méndez, A., & Watkins, F. (2023) The Hierarchy of Needs. Empirical Examination of Maslow’s Theory and Lessons for Development. World Development, 165, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106185

Russo, M.T., Argandoña, A., & Peatfield, R. (eds) (2023) Happiness and domestic life: the influence of the home on subjective and social well-being. Routledge Advances in Sociology.

Thomas, P., H. Liu & Umberson, D. (2017) Family relationships and wellbeing. Innovation in Aging. 1(3), 1–11. doi:10.1093/geroni/igx025

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: a meta‐analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574-583.

United Nations (1993) Household. Glossary of the 1993 Systems of National Accounts, Definition of terms. http://data.un.org/Glossary.aspx?q=household

United Nations (2019) Patterns and trends in household size and composition: Evidence from a United Nations dataset. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. (ST/ESA/SER.A/433).

United Nations (2021) World’s Women 2020. Population and families. Statistics. https://worlds-women-2020-data-undesa.hub.arcgis.com/apps/d5b5980632a8472a91211a7e94abcfb8/explore

US Census Bureau (2022) Census Bureau Releases New Estimates on America’s Families and Living Arrangements. Press Release Number CB22-TPS.99. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/americas-families-and-living-arrangements.html

Velázquez, L. & Ramírez, M. (2012). La familia en Caldas: Características e importancia para el bienestar subjetivo. RegionEs, 7(1), 7-42.

Velásquez, L. (2016). The Importance of Relational Goods for Happiness: Evidence from Manizales, Colombia. In M. Rojas (ed.) Handbook of Happiness Research in Latin America (91–112). Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-017-7203-7_6

Wadsworth, T. (2016). Marriage and subjective wellbeing: How and why context matters. Social Indicators Research, 126(3), 1025-1048.

Wall, K., & Gouveia, R. (2014). Changing meanings of family in personal relationships. Current Sociology, 62(3), 352-373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113518779

Watzlawick, P., Beavin Bavelas, J., & Jackson, D. D. (1967) Pragmatics of human com-munication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes. Norton.

You, W., Rühli, F. J., Henneberg, R. J., & Henneberg, M. (2018). Greater family size is associated with less cancer risk: An ecological analysis of 178 countries. BMC Cancer, 18(1), 924. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4837-0

Endnotes

Aknin et al. (2015); Rojas (2024). ↩︎

Bengtson (2001); Botha and Booysen (2014); Millán and Esteinou (2021); Wall and Gouveia (2014). ↩︎

An alternative explanation of reverse causality – happier people forming larger households – is explored; retrospective life satisfaction information from Mexico is used. The analyses suggest that the main causal directionality is from household size to happiness, rather than from happiness to household size. ↩︎

Beytía (2016): Russo et al. (2023); Velásquez (2016). ↩︎

McHale et al. (2003); Newman et al. (2016). ↩︎

Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991). ↩︎

Lomas et al. (2021). ↩︎

Beavin Bavelas (2021); Watzlawick et al. (1967). ↩︎

Referring to caring communities, Chapter 2 addresses a similar idea to this one. ↩︎

Oliva and Villa (2014); Rojas (2006). ↩︎

Rojas et al. (2023). ↩︎

Brown and Brown (2014); Thomas et al. (2017). ↩︎

Global studies on family configurations consider the household as the unit of enumeration for data collection. The United Nations defines a household as “a small group of persons who share the same living accommodation, who pool some or all of their income and wealth, and who consume certain types of goods and services collectively, mainly housing and food” (United Nations, 1993). ↩︎

Leyva (2014). ↩︎

Velázquez and Ramírez (2012). ↩︎

Montoya and Landero (2008). ↩︎

Millán and Esteinou (2021); Rojas (2024). ↩︎

Beytía (2017); Diener and Diener (2008); Florenzano and Dussaillant (2011); Moyano and Ramos (2007); Velázquez and Ramírez (2012); Wadsworth (2016). ↩︎

Nelson et al. (2014); Nomaguchi and Milkie (2020); Rojas (2018); Twenge et al. (2003). ↩︎

You et al. (2018). ↩︎

Barrera (1986); Barrera et al. (1981); Inglehart (2010, 2018); Inkeles and Smith (1976). ↩︎

Rojas (2024). ↩︎

Beytía (2017); Millán and Esteinou (2021); Rojas (2018, 2024). ↩︎

Esteve et al. (2023). ↩︎

Botha and Booysen (2014); Thomas et al. (2017). ↩︎

These trends emerge out of a variety of social, economic, and cultural factors, including, among others: declining fertility rates, longer life spans, later marriage and nonmarriage, higher divorce rates, delayed childbearing and childlessness, widowhood, and in general, a growing desire for autonomy and independence. ↩︎

Esteve et al. (2024). ↩︎

Fertility rates are projected to further decline worldwide, reaching a total fertility rate of 1.83 in 2100 (Bhattacharjee et al, 2024). ↩︎

Cohen (2021); Esteve et al. (2024); Ortiz-Ospina (2024). ↩︎

According to the United Nations (2021), since the mid-1990s, single-mother parenting has increased from 5% to 8% in Northern Africa and Western Asia; from 7% to 10% in sub-Saharan Africa, and from 8% to 10% in Latin America and the Caribbean, while the proportion of single-father households has remained between 1% to 2%. In selected OECD countries, 5% to 10% of households have children living with a single-mother and 1% to 3% of households have children living with a single-father. ↩︎

According to an analysis by Pew Research Centre (Cohn et al., 2022), the share of the US population in multigenerational households has increased from 7% in 1971 to 18% in 2021 (US Census Bureau, 2022). Data gathered by the United Nations (2019) indicates that multi-generation households are extremely common in many countries or areas in Asia (more than half in India and Pakistan), as well as several in sub-Saharan Africa. This type of household accounts for at least one in four households in all countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. In Europe and Northern America, multi-generation households represent more than 30% of all households in countries like Greece, Poland, Spain and Ukraine, but are rare in Canada and the UK. ↩︎

OECD (2016). ↩︎

The ENBIARE 2021 survey, generated by the national statistics office of Mexico (INEGI), asks the following question*: “Could you tell me, on a scale of 0 to 10, how satisfied you are currently with your life? 0 means “totally dissatisfied” and 10 “totally satisfied”.* Round 10 of the European Social Survey, applied in 2020 in 25 countries, asks the following question regarding life satisfaction: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays? 0 means “extremely dissatisfied” and 10 means “extremely satisfied”. The countries included in the ESS 2020 are: Belgium, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, United Kingdom, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, and Slovakia. Both questions and the response scales are quite similar. In any case, the empirical exercise does not compare across regions but explores the variability within regions. ↩︎

In a study in the Caldas department of Colombia, Velázquez and Ramírez (2012) arrived at similar results. The authors found higher levels of happiness among household heads and partners who live in households of four members. In this group of households, 69.5% of those surveyed rated their happiness as high or very high, which exceeds the levels reached in households with two, three, five and more members (between 60.0% and 65.8%) and particularly higher than single-person households (51.5%). ↩︎

OLS regressions are run. Life satisfaction is treated as cardinal. An alternative ordered-probit model was tested. The main conclusions of the research sustain when life satisfaction is treated as ordinal rather than cardinal. ↩︎

All the econometric models are run based on raw (unweighted) sample data. For the case of Mexico, the models were also run based on a weighted (expanded) version of the data. Both versions show very similar results. ↩︎

The control variables are age, age squared, gender, education level, and a constructed assets variable, which refers to the existence of the following goods and services in the household: refrigerator, washing machine, automobile, television, computer, video game, access to the internet, and access to any music and/or video streaming service. ↩︎

In this case, household income information is available for a group of European countries. Therefore, two models are run, one that includes income but relies on a smaller number of observations, and another that does not include income but uses a greater number of observations. ↩︎

Recommendations about the domains of life and their demarcation can be found in the OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being (OECD, 2013). ↩︎

Regression analyses similar to the one presented in Figure 4.5 (Table 4.1 of the online appendix) are followed. Satisfaction in the different life domains is the dependent variable. A quadratic specification for the number of household members is included and control variables in the regression are: age, age squared, gender, education level, and assets. ↩︎

Rojas (2024). ↩︎

Millán and Esteinou (2021). ↩︎

The ENBIARE survey defines a household as one in which one or more people live and share the costs and preparation of their meals. There may be cases where people physically share the same household, but do not participate in either spending on or preparing food (or do not do so all the time). There may also be households in which several families live, each sharing the cost and preparation of their food independently, but not necessarily together (or not all the time). Given the number of cases in these situations, the percentages are considered to be negligible for the purposes of the analysis conducted here. ↩︎

It is important to note that the same econometric exercise was applied to information that comes from two other reliable sources: the quarterly subjective wellbeing survey applied by the national statistics office of Mexico (INEGI) since 2014, known as BIARE Básico or Basic BIARE, and the quality-of-life survey applied by the national statistics office of Colombia (DANE) in 2023. In both cases, the results obtained are similar to those presented in Figure 4.10. ↩︎

The proportion of single-person households in Europe (24%) may be one of the factors behind the so-called loneliness epidemic in some European countries (Baarck et al., 2022). Despite its importance, to explore this possibility lies outside the scope of our analysis here. ↩︎

These analyses rely on information from the Understanding Happiness in Latin America survey, which involves three Latin American countries: Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico. ↩︎

These analyses are based on information from ENBIARE 2021 and consider the following variables: 1) considering that one can always count on the help of family members, 2) caring for or attending to family members who could not take care of themselves, 3) helping household members with their schoolwork or taking them to school, 4) frequency with which one usually has meetings with family members and 5) frequency with which one usually has meetings with friends of one’s partner. ↩︎

El Economista (2009). ↩︎

Barraza et al. (2009). ↩︎

In early 2010, after the killing of 14 children and young adults (and 15 wounded) in Ciudad Juárez, the authorities issued, and started the implementation of a new strategy to tackle the violence in Juárez, with an approach that went beyond policing and military action and included many social measures. The strategy was called Todos somos Juárez or ‘We are all Juárez’. See: Gobierno Federal et al. (2010). ↩︎