Connecting with others: How social connections improve the happiness of young adults

Chapter Contents

- Key insights

- Introduction

- Recent trends in wellbeing and social connection among young adults

- Regional patterns of social connection

- Temporal trends of social connection among young adults

- Social connection and wellbeing among young adults

- Literature review on social sources of wellbeing

- An in-depth study of one young adult community

- Open questions and future directions

- Conclusion

- References

- Endnotes

Key insights

- Social connection is vital for the wellbeing of young adults: Social connection buffers people from the toxic effects of stress and significantly enhances subjective wellbeing during young adulthood.

- Social disconnection is prevalent and increasing among young adults: In 2023, 19% of young adults across the world reported having no one that they could count on for social support, representing a 39% increase compared to 2006.

- Early social ties during young adulthood have long-lasting effects: For university students, forming friendships in the first few weeks of college can increase the likelihood of flourishing and reduce the likelihood of developing depressive symptoms over the subsequent years.

- Many young adults underestimate their peers’ empathy, leading them to avoid connecting with others and miss out on opportunities for meaningful relationships.

- Interventions can bridge this ‘empathy perception gap’: Field interventions that teach young adults about the empathy and care of their community can promote social connection. Undergraduate students exposed to these interventions see others as more empathic and are more likely to make new connections and build larger social networks.

Introduction

Young adults across the globe face increasing mental health challenges. Once considered one of the happiest phases of life, young adulthood has taken a troubling turn.[1] Young people in North America and Western Europe now report the lowest wellbeing among all age groups. In fact, World Happiness Report 2024 found that the fall in the United States’ happiness ranking was largely due to a precipitous decline in wellbeing among Americans under 30.[2]

This chapter centres on a key idea that illuminates the problem of low wellbeing among young adults and potential ways to reverse it: happiness is fundamentally social. Across cultures and generations, supportive relationships buoy mental health and happiness.[3] Social ties also buffer people from the toxic effects of stress,[4] reducing the risk that subclinical difficulties will escalate into mood disorders.[5]

But during the same period in which young adult wellbeing has declined, loneliness among this population has risen. A comprehensive analysis including 437 independent samples of young adults found that loneliness in this population has steadily increased over the past four decades.[6] This trend was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with young adults reporting greater feelings of loneliness compared to other age groups during that time. Even after the pandemic, contrary to expectations, young adult loneliness did not return to pre-pandemic levels. The US National College Health Association’s 2023 annual survey found that half of college undergraduates reported significant loneliness, representing a 4.7% increase compared to 2019.[7] Amidst busy campuses and despite a world saturated with instant communication, young people today report feeling increasingly distressed while lacking the connections that can help their psychological wellbeing.

In this chapter, we begin by presenting recent global patterns in social connection and wellbeing among young adults. Next, we review both classic and current research on community wellbeing, with a particular focus on young adults across the globe. We then zoom in on a large-scale, longitudinal project we have led, which explores social connection and wellbeing among multiple cohorts of one undergraduate student community across their four years at university. Data from this work advance the basic science of community wellbeing and provide avenues to improve it. We conclude by discussing open questions and how these research findings can inform policy to support the wellbeing of young adults worldwide.

As young adults strive for independence and transition to become less reliant on their family, they place greater emphasis on acquiring new friendships and expanding their social circles.

Recent trends in wellbeing and social connection among young adults

In this chapter, we define young adults as individuals in the age range of 18 to 29, a period that marks the transition from late adolescence to adulthood. This life period is often accompanied by significant environmental changes as well as psychosocial developments.[8] During this time, many young adults leave home for education, work, romantic relationships, or personal growth. On the other hand, many young adults — especially in parts of Eastern Europe and East Asia[9] — continue living with their parents. This pattern has become increasingly common in other countries such as the United States, reflecting increasing economic challenges for the young generation.[10] Contemporary cohorts of young adults have also grown up alongside significant societal developments which have changed the nature of human relationships, such as changes in communication due to social media and, more recently, large language models such as ChatGPT.[11] These experiences may add to young adults’ vulnerability to both loneliness and mental health difficulties.

In addition to changes in their environment, young adulthood is accompanied by important developmental milestones, including the establishment of new personal and professional relationships.[12] As young adults strive for independence and transition to become less reliant on their family,[13] they place greater emphasis on acquiring new friendships and expanding their social circles.[14] Historically, young adulthood has been one of the most social periods of life, as young adults tend to form more friendships and spend more time socialising than people in other age groups. In addition to fulfilling social needs, young adult relationships lay the foundation for psychological and social growth in later life stages, providing a network of support that can sustain wellbeing and resilience in years to come.[15] However, as we will explore, young adults have also faced a disproportionate decline in social connection in recent years, potentially impacting their wellbeing

Defining social connection

Social connection is a multifaceted construct that captures different aspects of how we relate to others. As shown in Table 5.1, it includes three dimensions: quantity, quality, and structure. Each of these dimensions plays a distinct role in shaping our wellbeing, offering unique pathways for fostering connection, belongingness, and support.

| Dimension | Description | Implications for wellbeing |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Number of existing relationships an individual has. This ranges from complete social isolation (having no relationships) to being connected to many others. | A larger number of social relationships can provide access to a larger pool of interactions, support, and resources. |

| Quality | Actual or perceived support (e.g., emotional, social, or financial) provided by relationships. | Quality social relationships can provide emotional satisfaction and perceived reliability of support. |

| Structure | Structural makeup of one’s social networks. One example is density, or how interconnected members of one’s social network are with each other. | Shapes the diversity, cohesion, and accessibility of social resources available to an individual. |

The Global Flourishing Study (GFS) and Gallup World Poll (GWP) datasets

To explore wellbeing and social connection among young adults, we draw on Wave 1 of the Global Flourishing Study (GFS),[16] collected between April 2022 and December 2023. This dataset includes responses from over 200,000 participants from 22 countries and one territory, spanning six continents and representing a wide range of cultures and geographies. The GFS covers a robust set of measures on wellbeing, health, social, economic, political, religious, spiritual, psychological, and demographic variables.

Notably, the GFS includes questions assessing the quantity and quality of respondents’ social connections. For the quantity of social connection, participants were asked whether they had at least one special person in their life that they felt very close to. This measure, framed as a yes-or-no choice, does not capture the full range in the quantity of a person’s connection, but it does help to identify people experiencing deep social isolation. With regard to the quality of social connection, participants rated the extent to which they could rely on other people in their lives for support when they needed help, using a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (always). The structure of individuals’ social networks, such as density, was not assessed in the GFS.

We also draw on the Gallup World Poll (GWP) to explore the temporal trends of social connection among young adults. The GWP dataset offers valuable insight into the quality of social connection by asking respondents whether they can count on their relatives or friends for support when they are in trouble. Importantly, the GWP has been tracking respondents on this measure for over a decade, allowing us to characterise changes in young adult social connection globally. Here, we utilise GWP data from 2006 to 2023, including over 661,000 observations from 168 countries.

Regional patterns of social connection

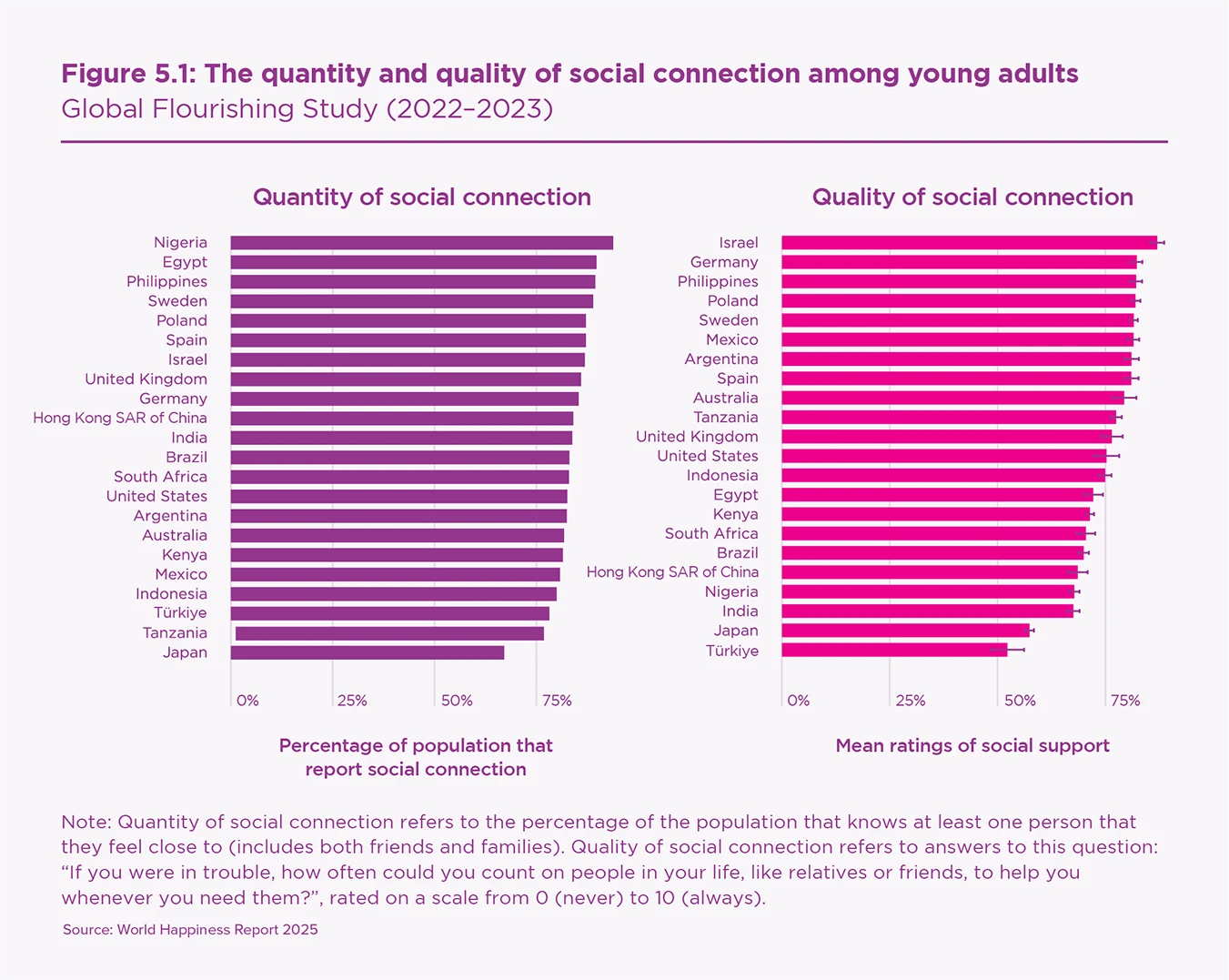

We begin by examining the current state of the quantity and quality of social connection among young adults across countries, and then compare the state of social connection across age groups. Data from the GFS demonstrate that while most young adults report having at least one social connection, a significant number are socially isolated. Across the 22 countries and regions, 17% of the young adult population report not having anybody (including family and friends) that they feel close to (Figure 5.1A). Japan stands out starkly, with over 30% of the young adult population reporting social isolation. In contrast, in countries such as Nigeria, Egypt, and the Philippines, less than 10% of the young adult population report having no close relationships.

Countries also varied in the quality of social connection reported by young adults. Participants rated how often they could count on people in their lives, such as relatives or friends, to provide help whenever needed. Overall, about 76% of young adults in the GFS sample reported that they can often count on people in their life for social support (indicated by a rating of 5 or higher on a 0–10 scale). Israel ranks the highest in the quality of social connections, followed closely by Mexico and Argentina (Figure 5.1B), indicating that young adults in these countries generally feel confident about the availability of help. By contrast, young adults in Japan and Türkiye report the lowest levels of social support.

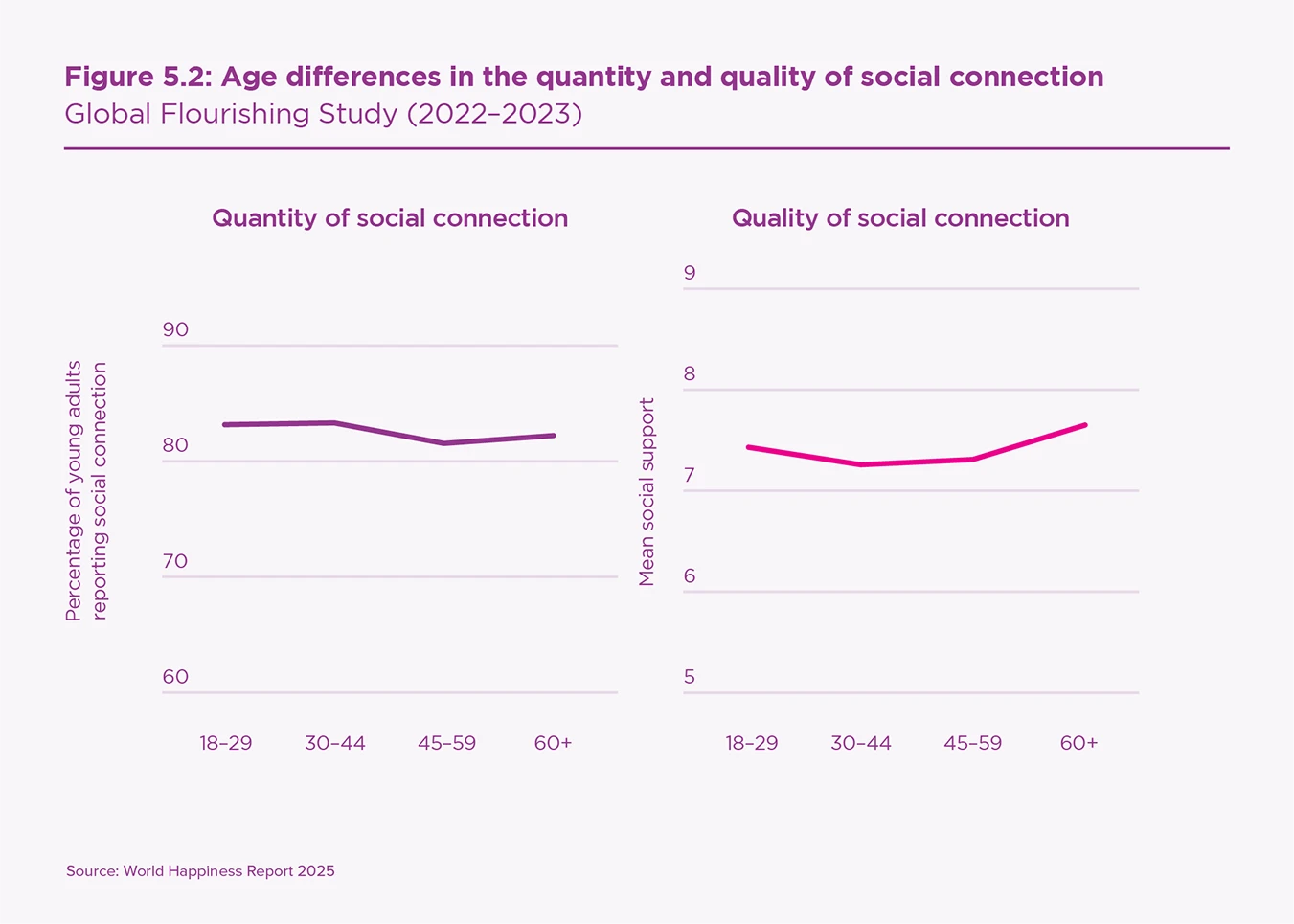

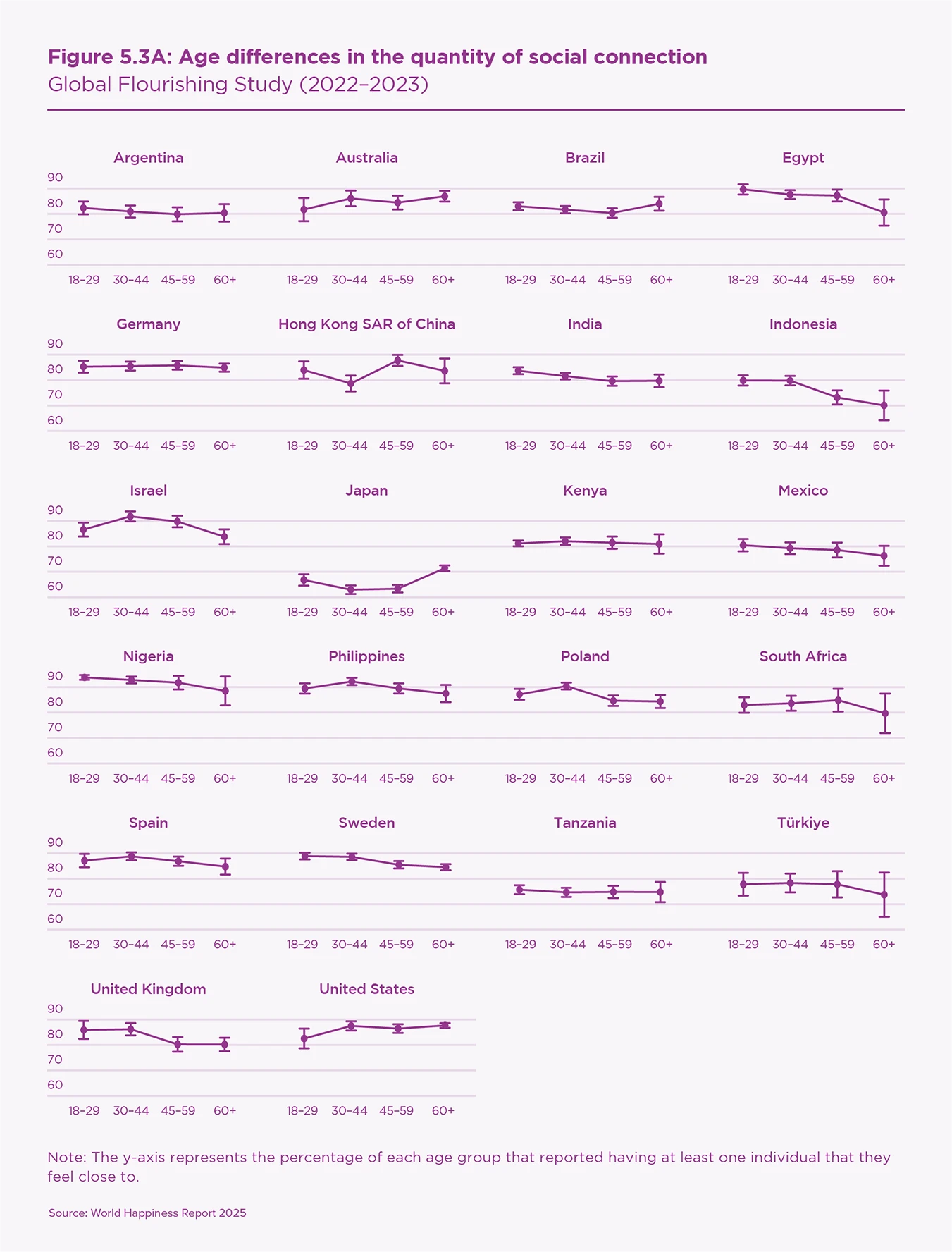

In Figure 5.2, we compare the social connection of young adults with other age groups. Consistent with previous observations,[17] adults older than 45 years report lower quantity of social connection compared to younger adults, representing higher levels of social isolation. For quality of social connection, the pattern follows a U-shaped curve, with both young adults (<30 years) and older adults (>60 years) reporting higher levels of social support. These patterns likely reflect the shifting priorities that come with age. Young adults often focus on expanding their social networks, while older adults may prioritise fewer but emotionally closer relationships, optimising their connections to benefit subjective wellbeing.[18]

Despite the overall trend that young adults report higher social connection than older adults, countries vary on the age-related differences in the quantity of social connection (Figure 5.3A). For example, this pattern is flipped in the United States, Japan, and Australia, where young adults report the lowest social connection among all age groups. In the United States, 18% of young adults (aged 18–29) reported not having anyone that they feel close to, whereas 15% of adults aged 30–44 reported no social connection.

Unlike other nations, young adults in the US also report lower quality of connection than other age groups (Figure 5.3B). Mirroring these patterns, World Happiness Report 2024 also highlighted a decline in the US happiness ranking, largely driven by a drop in wellbeing in the young adult age group.[19] Although not definitive, this provides intriguing preliminary evidence that relatively low connection among young people might factor into low wellbeing among young Americans.

Temporal trends of social connection among young adults

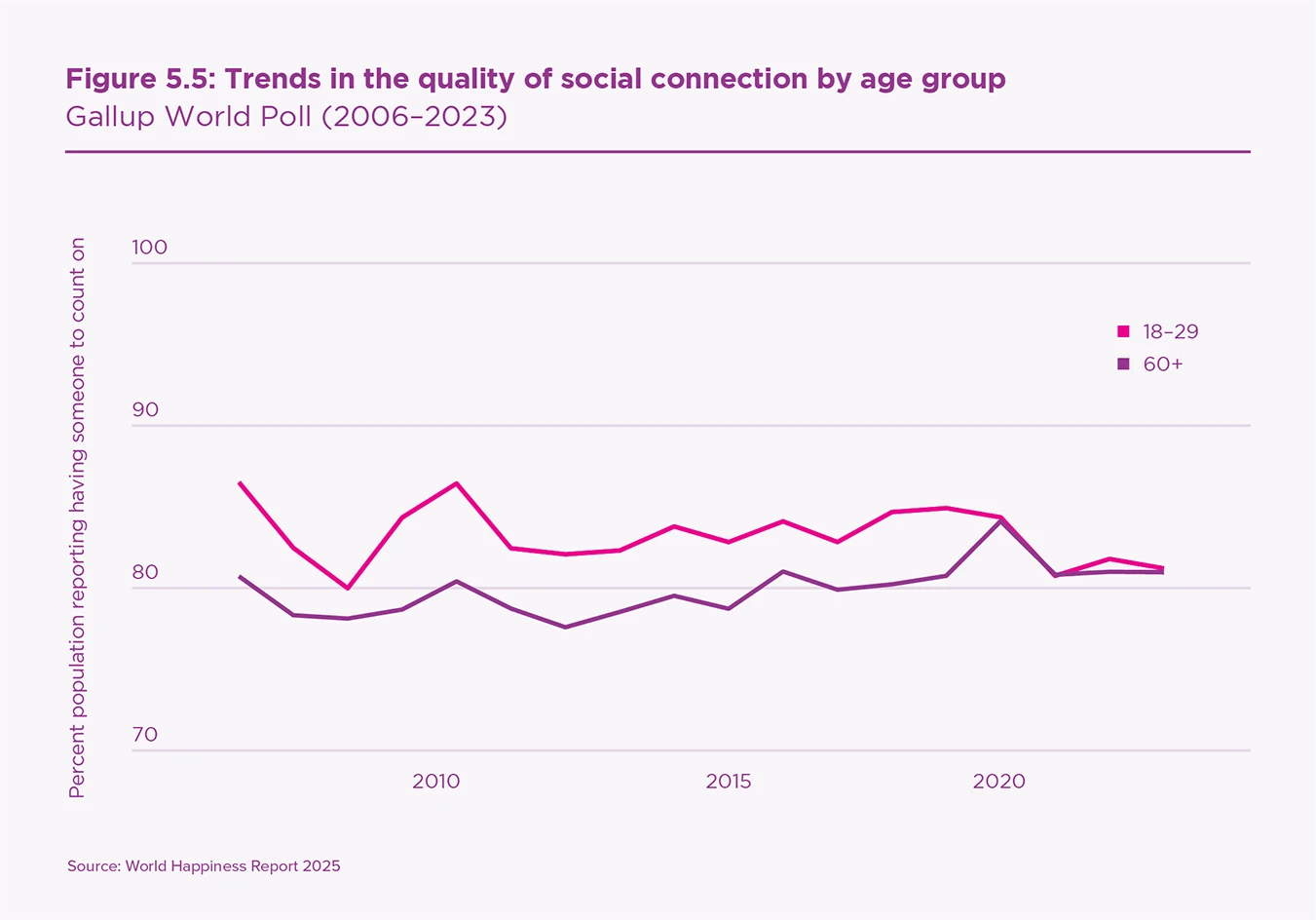

Recent reports suggest that young adults are experiencing a decline in social connection and a rise in loneliness.[20] Yet, our analysis of the GFS dataset showed that young adults are more socially connected compared to older age groups. At first glance, these findings may seem contradictory, but examining the data over time provides helpful context. If young adults in the past were even more socially integrated than they are now, this age group could face increasing isolation while still remaining more connected than older adults. In this section, we explore this possibility using the Gallup World Poll (GWP) dataset, which includes data from young adults across 168 countries from 2006 to 2023.

First, we observed an overall decrease in the quality of social connection among young adults over time (Figure 5.4A). Each year, an additional 0.1% of young adults reported not having anyone that they could count on. This may seem negligible, but globally it represents 1.7 million more young adults reporting they have no one to count on each year.

Next, we explore these trends within the 22 countries in the GFS survey (Figure 5.4B). Some countries (especially Tanzania) demonstrated significant decreases, mirroring the global trend. Yet, three countries (Mexico, India, and Egypt) bucked this trend, showing significant increases in the quality of social connection among young adults during this period.

As described above, young adults could be losing social connection over time but still remain more connected than older adults, which would be reflected in a shrinking age gap in connectedness. Indeed, when comparing the difference in the quality of social connection between young adults (18–29) and older adults (60+), this gap has decreased over the last 17 years (Figure 5.5). In 2006, young adults were 6% more likely than older adults to report having someone to rely on. However, since 2020, the difference between the two groups has fallen to less than 1%. This indicates that the decrease in quality of social connection is specific to young adults, and not observed across age groups.

Social connection and wellbeing among young adults

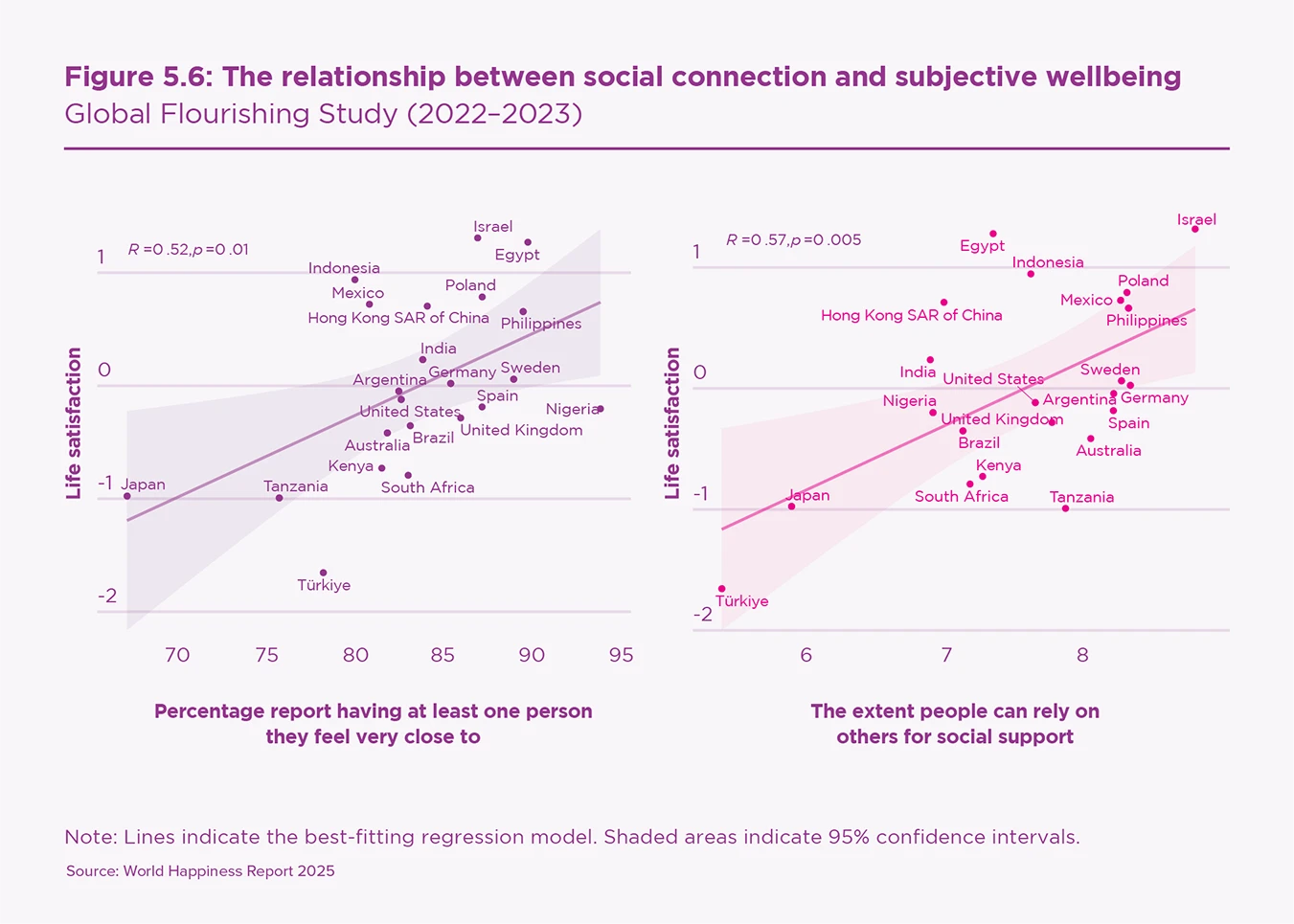

So far, we explored temporal and regional patterns of social connection in young adults. Next, we examine the relationship between social connection and subjective wellbeing within the GFS dataset. In the GFS, subjective wellbeing was measured with the following life satisfaction question: “How satisfied are you with life as a whole these days?” Responses were rated on a scale from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied). We find that countries where young adults report general higher levels of social connection and social support also report higher life satisfaction (Figure 5.6). This relationship was independently observed for both quantity and quality of social connection.

The link between social connection and wellbeing is not only observed at the national level but also for individuals. On average, young adults who report higher levels of both quantity and quality of social connection tend to feel more satisfied with their lives. Individuals who reported having at least one person they are close to are 16% more satisfied than individuals with no close contacts.[21]

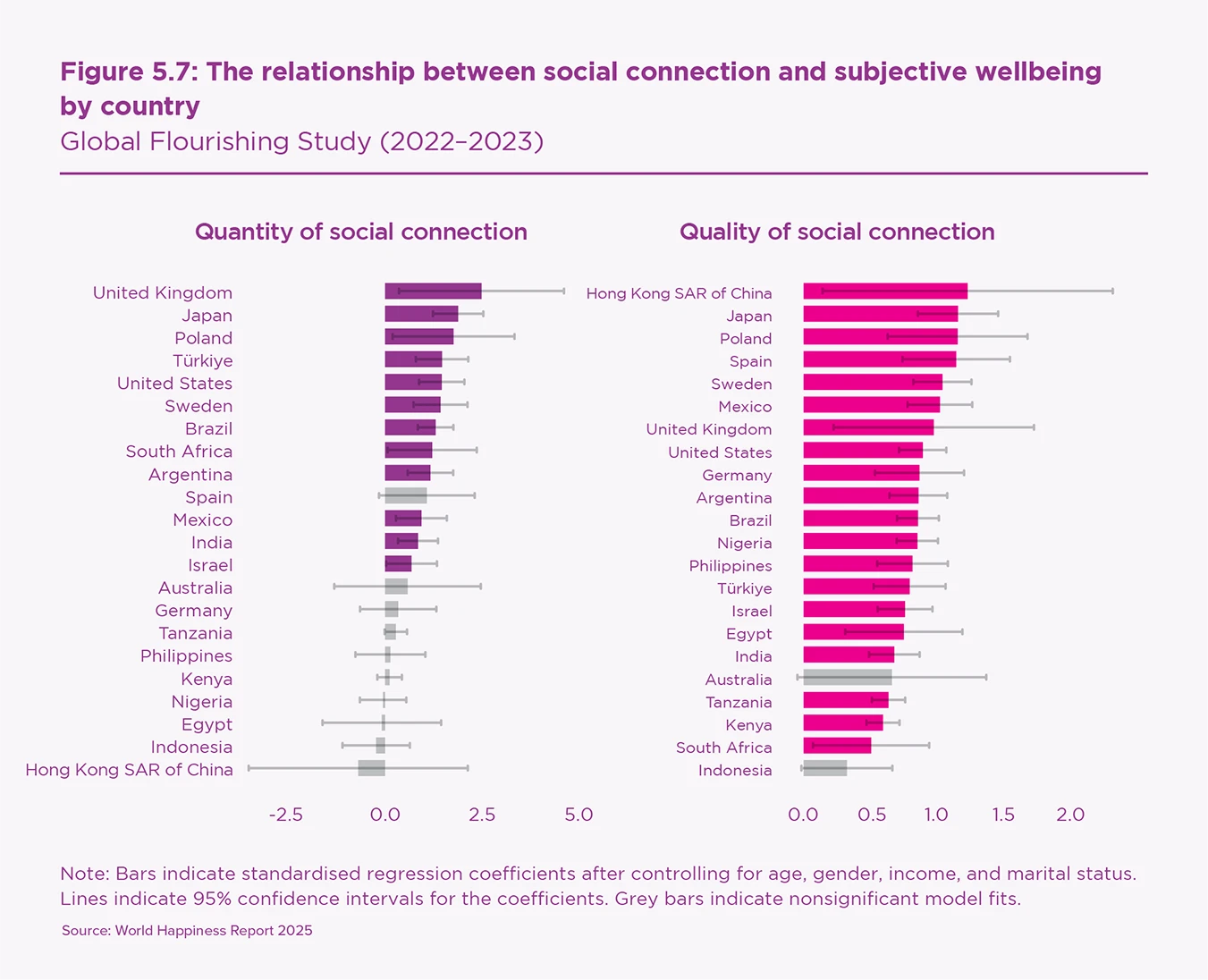

In a few countries which scored highest on social connection (such as Nigeria and Egypt) we do not observe significant associations between social connection and wellbeing (Figure 5.7). For example, over 90% of young adults in Egypt reported having at least one person that they feel close to. Because only a small proportion of this group reports lacking social connection, it’s difficult to relate social connection with wellbeing among this group.

Similarly, we observe a significant positive association between the quality of social connection and wellbeing. A 1-point increase in perceived social support is associated with a 0.29-point increase in life satisfaction.[22] Data from all 22 countries and regions in the GFS data showed a positive association, although the size of this positive association varied slightly across countries.

When these two factors of social connection are entered in the same model to predict life satisfaction, both the quantity and quality of social connection were significantly associated with life satisfaction, with comparable effect sizes.[23] This result indicates that the quantity and quality of social connection independently predict life satisfaction.

In the following sections, we present further evidence on the links between social connection and happiness, as well as the potential barriers preventing young people from fostering connections.

Literature review on social sources of wellbeing

Longitudinal tracking of young adult social connection

Social connection correlates with wellbeing both among individuals and across countries. These correlations raise an important question regarding causality: do healthy social relationships lead to greater wellbeing, or does feeling happy make people seek out social connections, or are these both true?[24] To characterise the direction of these relationships, it is important to go beyond measuring connection and wellbeing at a moment in time. For instance, researchers can track the same individuals over time to see if social connection predicts better wellbeing in the future, or if the reverse is true. Studies that take this approach indeed find that when people are socially connected, they are more likely to thrive in the future.

Consider the Harvard Adult Development Study, a long-running research project that investigates how individuals’ health and wellbeing evolved as they grew up.[25] This program started in 1938 with 724 university students. Researchers continue to monitor the wellbeing of the original participants who are in their late 90s now. Over the years, the project expanded to include larger cohorts of participants. For over 80 years, researchers have tracked the participants’ lives, collecting data on their health, relationships, and overall wellbeing through periodic interviews and medical checkups. One of the study’s most significant findings is the importance of social relationships for long-term happiness and health. Researchers found that the people who stayed the healthiest and lived the longest tended to be those who had the strongest connections to others. For example, close relationships were found to delay mental and physical decline, and were better predictors of long and happy lives than social class, IQ, or even genetic factors.[26]

Studies that take this approach indeed find that when people are socially connected, they are more likely to thrive in the future.

Other studies with wider population samples have also found a similar link. Social connection predicts later increases in life satisfaction and this holds after controlling for a wide range of demographic variables and stress.[27] In one study, using a large representative survey in Germany, researchers asked participants to report on their ideas for how they could improve their life satisfaction. The researchers then investigated which ideas predicted changes in life satisfaction one year later. The researchers found that those who had socially engaged goals (e.g., “I plan to spend more time with friends and family”) often reported improvements in life satisfaction one year later. In contrast, those who had other goals (e.g., “I plan to find a better job”) did not report increased life satisfaction.[28]

Social relationships are also significant predictors of wellbeing in longitudinal analyses of young adults specifically. In one study, researchers tracked 393 US students across their four years of university on a number of social factors as well as life satisfaction.[29] Students who were more extroverted reported higher life satisfaction four years later, in part because they formed stronger social connections in the university. In addition to social connection, several studies conducted across cultures including the US, Portugal, Germany, Russia, and China found that students who report receiving more social support also reported higher wellbeing later in college.[30]

You might expect that extroverts would derive greater joy from social interactions, but evidence suggests that both extroverts and introverts derive happiness from social interactions, but for different reasons.

In addition to tracking individuals over long periods of time, recent studies have captured data over shorter but more intensive periods, such as days or weeks. This is done by briefly surveying participants multiple times per day (an approach called ‘experience sampling’) or passively collecting data from individuals (such as background sound from their mobile phone, an approach called ‘passive sensing’). For example, researchers sometimes ‘ping’ participants throughout the day to assess their behaviour (e.g., whether the participant engaged in a social interaction) and whether they feel happy at that moment. These studies find that people generally feel happier after they engage in social interactions.

Experience sampling also allows researchers to examine who benefits most from social interactions. For example, you might expect that extroverts would derive greater joy from social interactions,[31] but evidence suggests that both extroverts and introverts derive happiness from social interactions, but for different reasons. Extroverts tend to experience a boost in mood after spending time with others. Introverts, on the other hand, tend to feel a stronger sense of connectedness after interactions, especially when those conversations are meaningful and deep.[32]

Experience sampling can also reveal when social interactions improve wellbeing. In one recent study, Krämer and colleagues tracked German-speaking participants with experience sampling and passive mobile sensing. Participants generally felt happier after social interactions, but this was only the case when the social interactions were aligned with their needs. For example, when people were socially interacting while desiring to be alone, they experienced decreases in happiness. On the other hand, when individuals deliberately engage in social interactions to seek comfort, celebrate, or commiserate, these connections tend to increase wellbeing.[33]

These studies provide robust evidence that people feel increased happiness after connecting and interacting with others.

There is strong evidence that social connection is followed by greater happiness, but what about the reverse? Does being happy lead people to seek the company of other people? The relationship between happiness and social behaviour appears to be more nuanced. People do tend to report feeling more social when they are in a happier mood,[34] but they also tend to seek contact with others in times of distress.[35] This pattern suggests that we turn to others for different reasons depending on how we feel. When we are feeling down, we may seek out happiness-enhancing social relationships. On the other hand, when we are feeling good, we might be more willing to share this happiness with others or invest in less enjoyable social interactions – like resolving conflicts or developing new relationships – that could bring long-term benefits.[36]

Together, these studies provide robust evidence that people feel increased happiness after connecting and interacting with others. While these studies help us understand the correlation between social connection and happiness, it is important to note that they cannot establish social connection as the sole reason causing this positive boost in mood.

Causal links between social connection and wellbeing

Examining social interaction and happiness across people, or within people over time, provides intriguing links between these experiences. But to better understand if social interaction causes greater wellbeing, scientists need to conduct experiments that randomly assign participants to engage in social connection or not. One specific type of social behaviour, prosocial behaviour, has already been covered in Chapter 4 of World Happiness Report 2023.[37] But can other forms of social connection help protect against the harmful effects of stress and elevate happiness?

In difficult times, social connections act as a protective shield against the harmful effects of stress.[38] A series of experimental studies from the past two decades provide evidence that receiving social support (compared to no support) can buffer the negative impact of stressful events. These studies generally put participants under distress, such as applying a mild electric shock or giving a speech in front of others, and record participants’ stress levels under different experimental circumstances.

In a series of classic experiments,[39] young adult participants were randomly assigned to deliver a speech either with or without access to social support. Participants in the social support condition exhibited lower blood pressure, a physiological indicator of stress, compared to those who did not have access to social support. This suggests that the presence of social support can mitigate physiological stress responses during stressful tasks.

More recent studies corroborate this effect with brain evidence. In one experiment, young adults received mild electric shocks while their brain activity was recorded in a fMRI scanner.[40] Each participant received these shocks either alone or when holding hands with an opposite-sex companion, such as a friend or romantic partner. Overall, when participants were holding hands, they rated the experience as less distressing and exhibited less activity in brain regions associated with the experience of threat.

Even when people cannot directly access their support systems, simply imagining the presence of a caring friend or loved one can soothe the distress of experimentally-induced pain.[41] In one experiment, participants viewed a picture of a loved one while experiencing mild pain from heat stimulation. Compared to viewing a picture of an object, seeing the photo of a loved one reduced their pain perception just as much as physically holding a partner’s hand.

In addition to dampening stress, social interactions can be a powerful driver of happiness too.[42] When the adventurer Christopher McCandless faced his own eventual death after months alone in the Alaskan wilderness, one of his last reflections was “happiness is only real when shared”.[43] While his experience may be extreme, people do tend to share their joyful moments with others to elevate happiness – a process called capitalisation.[44] For example, compared to those who wrote about a positive event privately, or shared this event with unresponsive peers, participants who shared this event with responsive others reported these events to be more positive and personally meaningful, demonstrating the power of social sharing in enhancing happiness and meaning.[45]

The benefits of social interaction go beyond sharing good news with friends and family. Even general interactions with strangers, though potentially nerve-wracking, can spark joy. In one study, some university students were instructed to either spend 30 minutes interacting with peers they did not know or to stop interacting whenever they wanted and to spend the remaining time sitting in solitude.[46] Students who were assigned to interact with strangers for the entire 30 minutes enjoyed the time more than participants who were allowed to spend some of the time in solitude. Thus, even brief interaction with strangers can elevate happiness.

30-minute conversations with strangers might be rare, but our day-to-day lives are filled with brief encounters: thanking the barista preparing our morning coffee, asking someone for directions, or exchanging a few words with a fellow commuter on a bus. Would something as simple as saying “hi” or “have a nice day” to these strangers contribute to happiness? Research on these “minimal social interactions” shows that even small exchanges with strangers can enhance happiness. In a study involving 265 Turkish university students and staff, the students who were asked to thank, greet, or express good wishes to their shuttle bus drivers experienced greater happiness than those who were asked to not speak with the drivers.[47] Similar effects were observed for bus and train commuters who were instructed to interact with a fellow commuter,[48] as well as customers at Starbucks who were instructed to have a brief social interaction with the barista, compared to those who were not asked to interact.[49] Together, these findings underscore that even brief interactions with strangers can buoy happiness.

Going beyond a single instance of socialising, a few studies have examined how being social for weeks can impact long-term happiness. For instance, one study investigated the benefits of acting more extroverted.[50] 114 Australian adults were randomly assigned either to act more extroverted (bold, outgoing, and talkative) or more introverted (quiet, sensitive, and calm) for a week. Those who acted extroverted experienced more positive moods compared to those who acted introverted. Even individuals who were more introverted by nature experienced more positive emotions when they acted more outgoing. Interestingly, this improvement in happiness was not due to more social interactions, but because of the way people behaved during them.

A network science approach to social connection

The evidence and data reviewed so far concern direct connections between people. Yet, our social world extends beyond our direct connections. A wealth of research reveals that the structure of a person’s social network – the way that their relationships are organised – is also associated with wellbeing. These studies often employ a network science approach,[51] where individuals (or ‘nodes’) in the social network are connected by relationships (or ‘ties’) to form complex networks of social relationships. This type of diagram intuitively characterises how people connect and allows researchers to develop precise mathematical metrics that capture the structural composition of these networks. Such metrics can reveal important insights into someone’s social world that would otherwise remain hidden, offering a more nuanced picture of how our social worlds may shape our capacity to thrive.

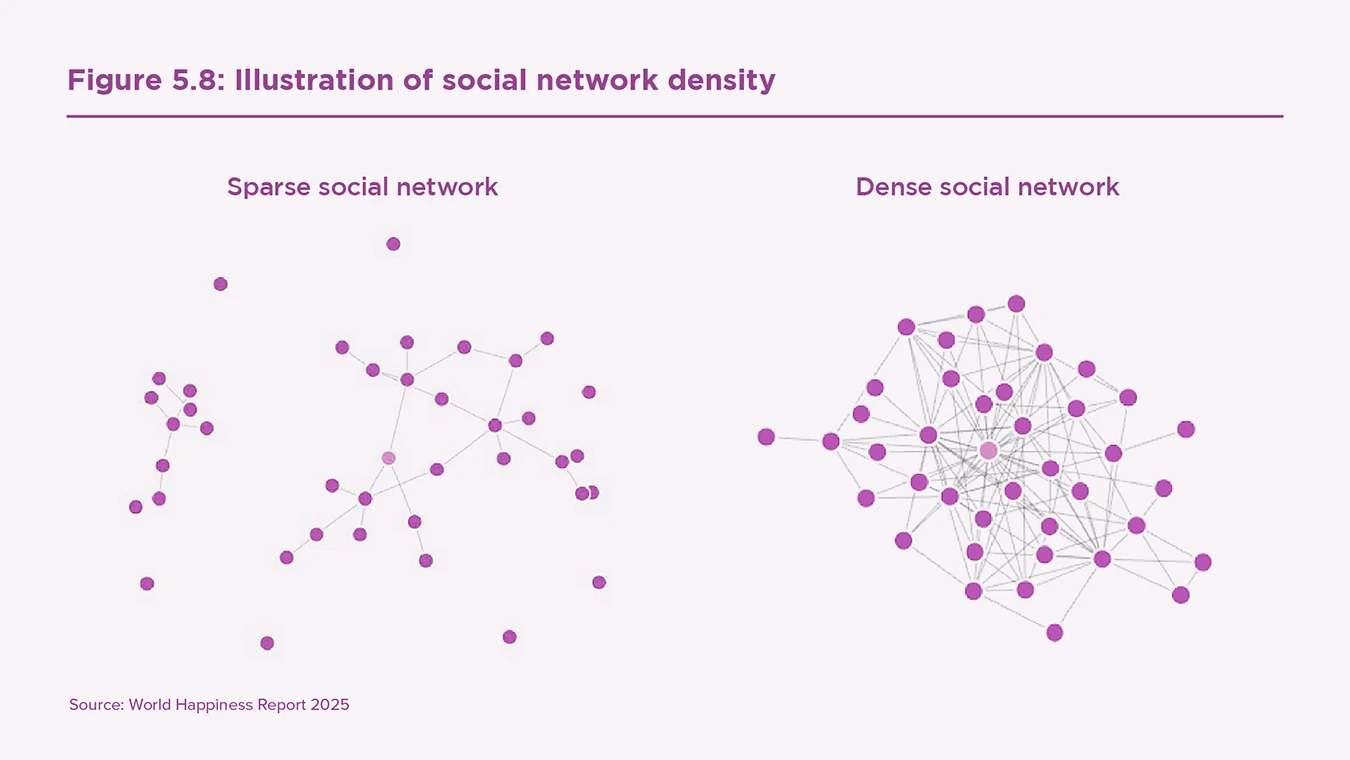

One network metric is density, the level of interconnectedness between nodes in a social network (Figure 5.8).[52] People who are situated in dense social networks tend to be less lonely and happier,[53] perhaps because these dense connections offer a sense of security, stability, and belonging.

In one recent study, researchers interviewed 2,485 individuals in Indiana, USA across three years during the COVID-19 pandemic.[54] In addition to wellbeing measures, they also assessed characteristics of the participants’ social networks, such as size, closeness, and density. Overall, young adults were disproportionately affected by the pandemic, reporting larger drops in wellbeing compared to other age groups. Interestingly, young adults with more dense and interconnected social networks experienced smaller decreases in wellbeing compared to those with sparser networks. This buffering effect of social network density was stronger for young adults compared to other age groups.

Another aspect of social network characteristics that may contribute to mental health is diversity, the extent to which individuals connect with different groups of people. Diverse networks, which include a mix of close family ties and different types of peers (e.g., members of the orchestra, track team, and culinary club), can protect against depression and other mental illnesses.[55] Interacting across group boundaries – such as differences in race or socioeconomic status – further amplifies these benefits. These connections foster a sense of belonging and can help reduce feelings of exclusion, especially for individuals from minority groups.[56]

Interacting across group boundaries – such as differences in race or socioeconomic status – further amplifies these benefits.

A recent analysis including over 24,000 adults in England paints a nuanced relationship between social network diversity and subjective wellbeing.[57] While some level of network homophily (similarity between contacts) is linked with better wellbeing, social networks that are excessively homogeneous can undermine happiness. This finding underscores that a balance between homophily and diversity – combining in-group familiarity and out-group variety – may offer the greatest advantages and enhance subjective wellbeing.

In summary, work in this area so far demonstrates that the quantity and quality of social connections, along with the structure of social networks, shape wellbeing. Social networks that are dense and diverse can offer psychological security, belongingness, and opportunities for growth, all of which can elevate subjective wellbeing.

An in-depth study of one young adult community

The evidence we have reviewed so far provides strong support for the old proverb: “shared joy is a double joy; shared sorrow is half sorrow.” Yet, recent studies and our new analysis paint a sobering picture: young adults globally are lonelier than before.[58]

While young adulthood is expected to be one of the happiest and most social life stages, young adults in the US reported the lowest happiness and social connection of all age groups. If social connection is so beneficial, why are young adults not connecting more? Answering this question will require more in-depth assessment of young adults’ beliefs and attitudes towards their community. This section presents insights from our large-scale, longitudinal project, the Stanford Communities Project (SCP).

The goal of the SCP is to provide a detailed assessment of the social health of one young adult community. Since 2018, the project has assessed thousands of Stanford undergraduates, multiple times a year, to gather data on personality traits, wellbeing, social networks, and momentary assessments of social activity. The SCP provides a novel and comprehensive means to examine perceptions, social behaviour, and mental health in a young adult population. So far, the findings from this project underscore the profound impact of social connection on happiness and wellbeing, but they also highlight a critical gap: young people experience diminished connection when they perceive their peers as less empathic than their peers self-report. By examining this ‘perception gap’ and trying to reduce it, we can better understand how to foster meaningful connections and support the wellbeing of young adults.

Early social ties have long-lasting effects on wellbeing

As we reviewed above, scientists often track individuals over time to uncover the longitudinal link between social connection and wellbeing. The SCP did the same by following two cohorts of undergraduate students (N = 1,061) across their college years. Twice a year, we assessed changes in the students’ friendships and wellbeing and found five distinct wellbeing trajectories that students followed during college. For example, some students experienced improving wellbeing (‘getting better’), and others experienced worsening wellbeing (‘getting worse’). Notably, 38% of students followed the ‘getting worse’ trajectory, where symptoms of depression intensified over the course of college.

We found that the number of social ties a student forms in their first few weeks of college predicts the long-term trajectory in the subsequent years. Every additional friendship was associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of ‘getting worse’ compared to ‘getting better’. This highlights the protective role of social connection during a critical time of transition.

The impact of friendships lasted well beyond those first few weeks. Across the college years, friendships change in interesting and meaningful ways, shaping the wellbeing trajectories that students may follow. Each new friendship increases the likelihood of ‘getting better’ by 17%. On the other hand, losing a friendship increases the chances of falling into a ‘getting worse’ trajectory by 19%. These findings add to existing evidence that stronger social connections are usually followed by better wellbeing down the road.

Cohesive ‘social microclimates’ support wellbeing

An individual’s direct friendships contribute to their wellbeing. As we have seen, existing evidence suggests that tight-knit social circles can offer a sense of security and belonging, thus promoting mental health. But what happens when we zoom out to consider the larger social ecosystem that students inhabit? Each person resides in a unique ‘social microclimate’, characterised by the emotional traits of friends and community members, as well as the relationships among neighbours. Unlike direct friendships, a young adult’s social microclimate is often beyond their control. Yet, various features of this microclimate can significantly affect their subjective wellbeing.

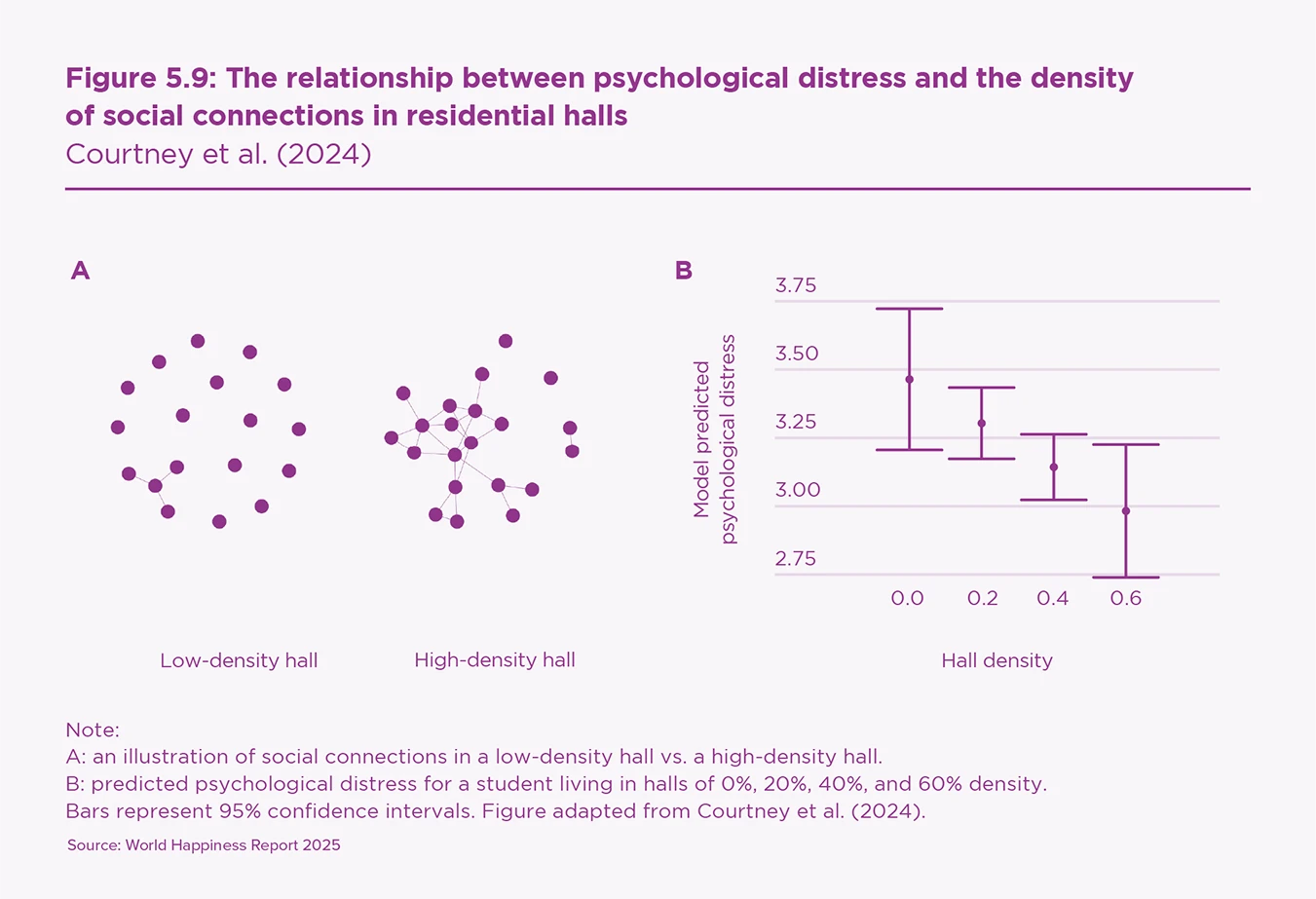

To test this hypothesis, our team leveraged an assignment process that many universities use for student housing.[59] At Stanford University, all first-year students were assigned to residential halls. This offers a unique opportunity to study how social microclimates shape wellbeing while controlling for the confounding factor of individuals selecting their own social groups. Since students did not choose who would live in the same hall with them, the researchers could isolate the effect of the broader social ecosystem from the effects of the direct, personal connections.

Unlike direct friendships, a young adult’s social microclimate is often beyond their control. Yet, various features of this microclimate can significantly affect their subjective wellbeing.

We collected data from 798 first-year students and assessed their personal traits, such as emotional stability and empathy, before the students arrived on campus. Midway through their first term, students were asked to report their subjective wellbeing and nominated their friends. This allowed us to capture two types of social factors. The first type consists of a student’s direct social network: how many friends they had and how supportive and empathic those friends were. The second type concerns the social microclimate, which includes not only direct personal ties, but also the hallmates that the student is not directly friends with. For instance, we measured the overall density of social connections within each hall. A hall with high density would have many students nominating each other as friends, creating a more cohesive microclimate (Figure 5.9A).

The results showed that these social factors significantly influenced wellbeing. Consistent with the evidence reviewed above, attributes of a student’s direct social network are significantly associated with subjective wellbeing. Moreover, the density of a student’s social microclimate also plays a significant role in mental health. Students who lived in high-density halls, where community members are more interconnected, reported lower levels of psychological distress and higher life satisfaction (Figure 5.9B). These effects remained robust even after accounting for individual traits and characteristics of one’s direct social network. Thus, the density and cohesion of a student’s social microclimate may also shape subjective wellbeing, as well as their immediate social network.

Gaps in social perceptions hinder social connection and wellbeing

Close friendships and cohesive communities buoy happiness. Yet, even in supportive communities, people can still feel isolated and hesitate to reach out to others. As we described above, feelings of loneliness for young adults have increased by an average of 0.22% per year for the past four decades,[60] and the quality of social connection has decreased for young adults since 2006.

If social connection brings so many benefits, why do so many young people still feel lonely? Part of the answer may lie in their perceptions of others and their communities. Findings from new research reveal that inaccurate social perceptions can be a barrier for social connections. For instance, people tend to underestimate how fulfilled and happy they will feel after interacting with strangers,[61] having deep conversations with friends,[62] expressing gratitude,[63] giving compliments,[64] and asking others for help.[65] In short, people are not very accurate in forecasting how they will feel after engaging in social activities, leading them to miss out on opportunities to connect.

People are not very accurate in forecasting how they will feel after engaging in social activities, leading them to miss out on opportunities to connect.

We hypothesise that there may be other factors at play in addition to inaccurate forecasting of future feelings. Perhaps people are not only misjudging their own emotional outcomes but also holding inaccurate beliefs about others and their communities. For example, students may underestimate the empathy and care in others, and this empathy perception gap might leave individuals socially risk averse and ultimately more isolated.

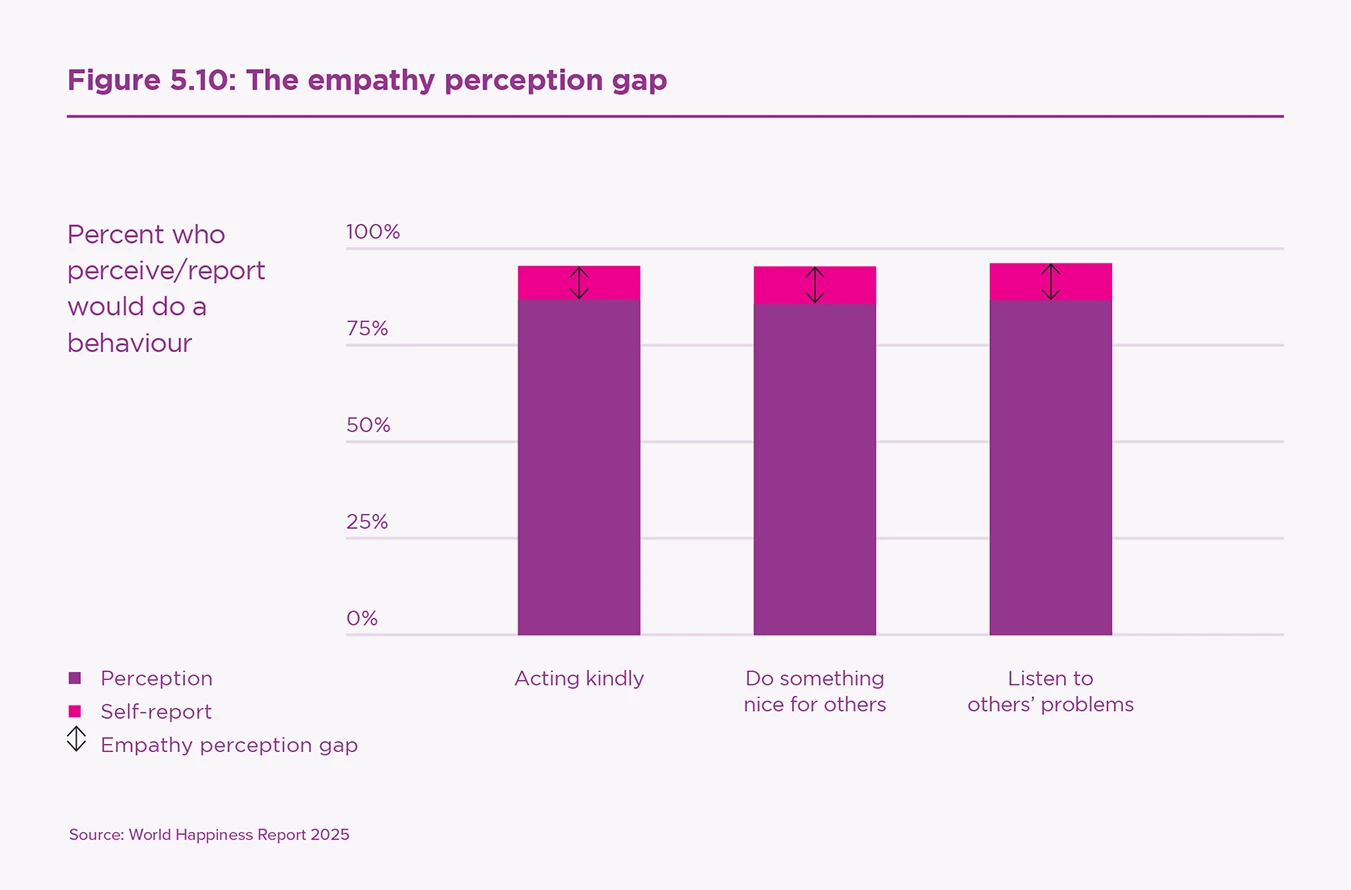

We tested this hypothesis using data from the SCP.[66] Drawing from two years of data involving over 5,000 undergraduate students, we assessed two types of data related to community empathy. First, we assessed ‘empathy perception’, where students estimated the empathy of their peers. We also asked about their own levels of empathy. By combining these two types of data, we can assess whether students’ perceptions matched their peers’ self-report.

Our results indicate a persistent empathy perception gap. Students tend to view other students as less empathic and caring than their peers see themselves. For instance, participants estimated that 87% of Stanford students would “act kindly by helping others who are feeling bad”, whereas 96% of Stanford students responded positively to the same question, indicating a 9% empathy perception gap on this measure (Figure 5.10).

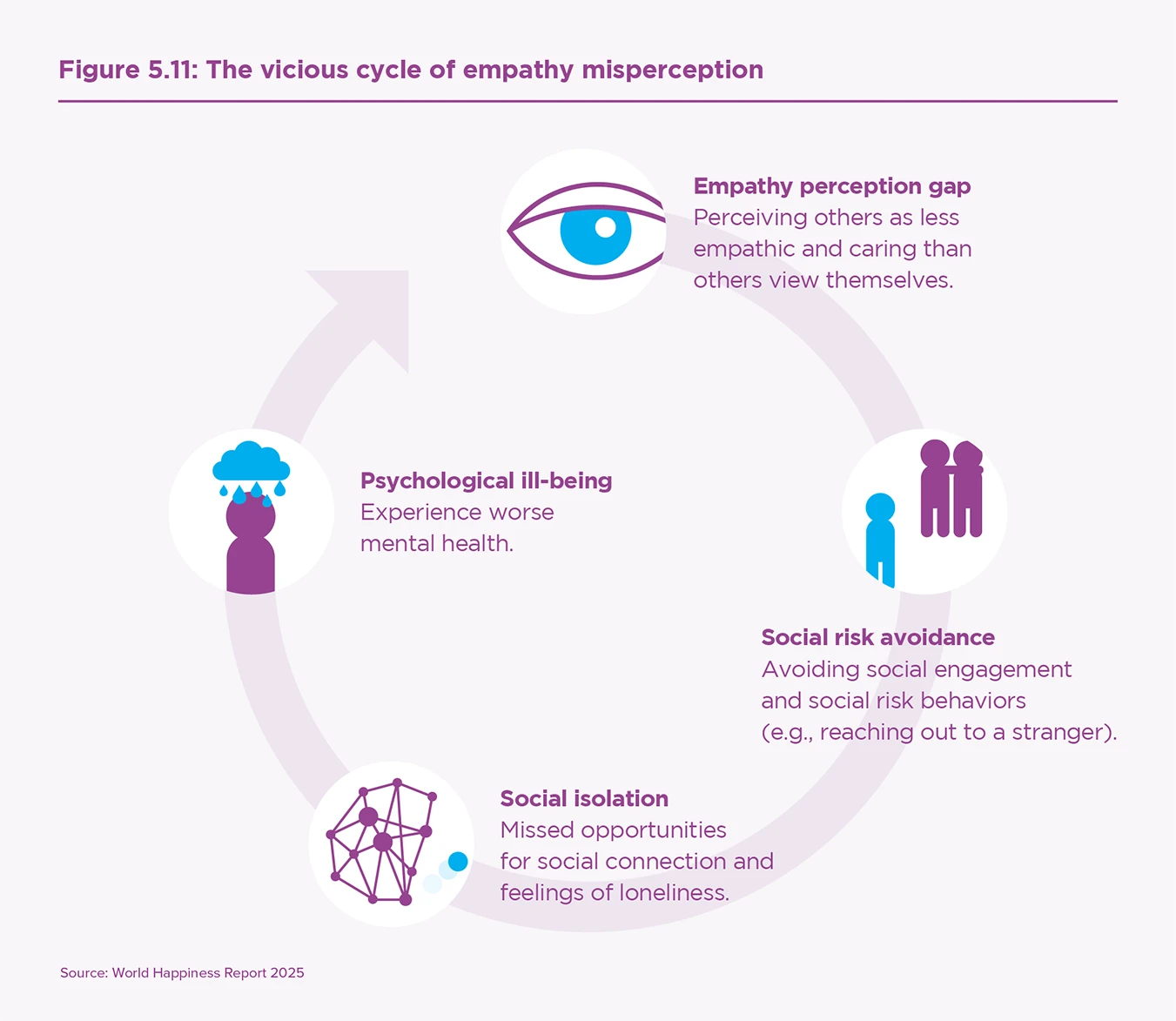

The consequences of this empathy perception gap were profound. Students who perceived their peers as less empathic and supportive were less likely to take social risks such as striking up conversations, sharing personal struggles, or reaching out for help; behaviours that are critical for building meaningful relationships. This social risk avoidance led to missed opportunities to connect and learn from others, perpetuating the misguided belief that those around them lack empathy and care. Over time, this empathy perception created a vicious cycle of misperception and social disconnection (Figure 5.11).

Campaigns to align perceptions can foster social connection

Empathy perception gaps help explain why young people are socially isolated and lonely. They also illuminate a potential opportunity to break the vicious cycle and promote social connection. When individuals view the people and community that surround them as supportive and caring, they are more likely to take the social risks of reaching out to strangers and seeking social support. Taking these social risks can help foster meaningful connections, expand social networks, and improve wellbeing.

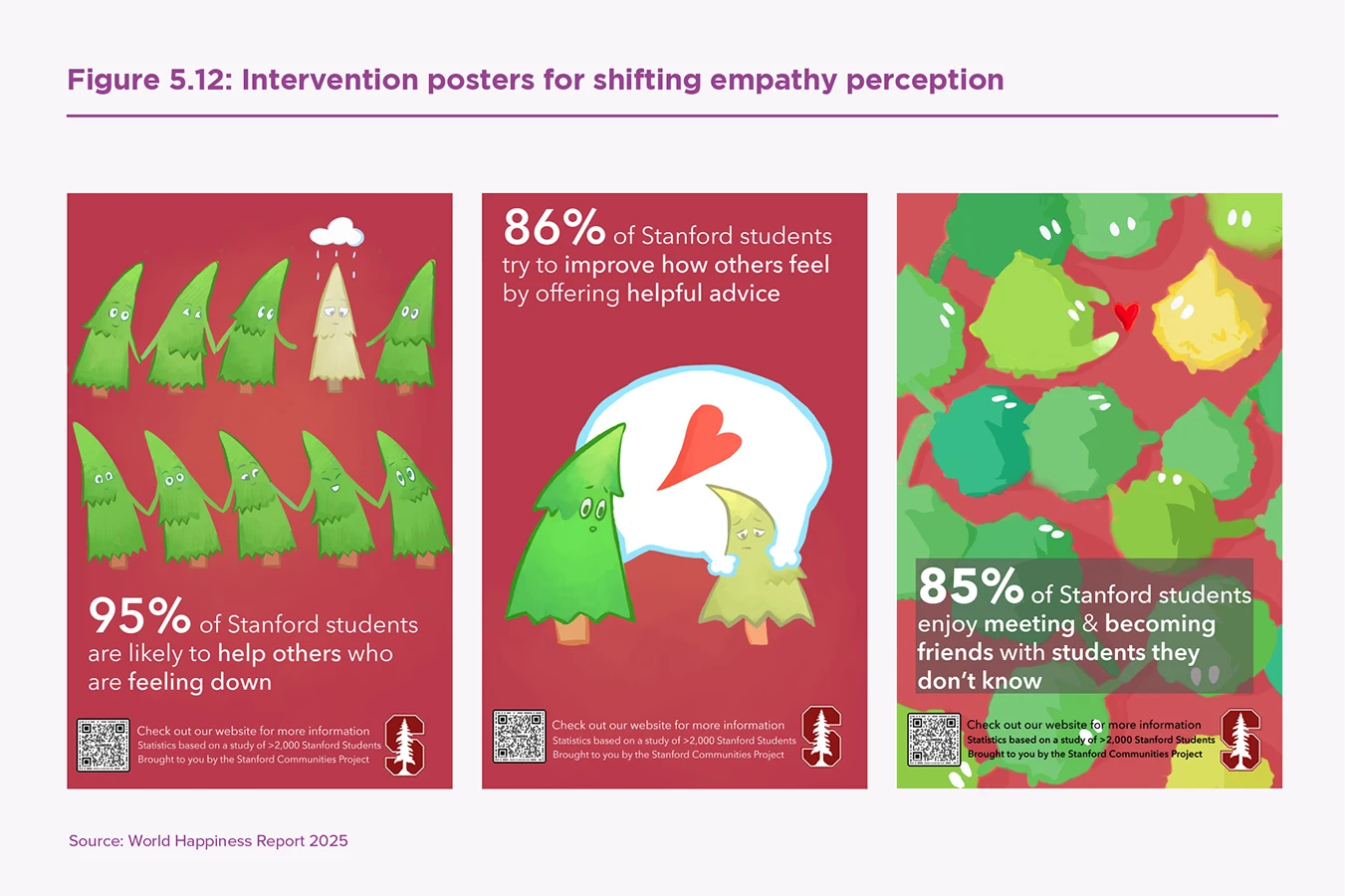

Over the past two years, we have pioneered a new intervention to enhance social connection by addressing the perception gaps and providing opportunities for students to learn about the care and support in their community. We did this using two field experiments.

In the first field experiment, we presented students with data about their peers’ high levels of empathy and interest in making friends. To do this, we put up posters around residential halls with statistics like “95% of Stanford students are likely to help others who are feeling down” (Figure 5.12). We paired the posters with a one-hour educational workshop designed to reinforce the message that their peers were more caring and supportive than they might think.

Students exposed to this data significantly shifted their perceptions. On average, participants in the control condition underestimated their peers’ empathy by 0.4 points (on a 7-point scale). Participants in the experimental condition still underestimated their peer’s empathy (by 0.1 points), but slightly less than participants in the control condition, representing a 75% reduction. Students also reported taking more social risks following our intervention – they reached out to classmates they didn’t know, initiated conversations, and were more willing to share their vulnerabilities. On average, the frequency of these social risk behaviours increased by 11%.

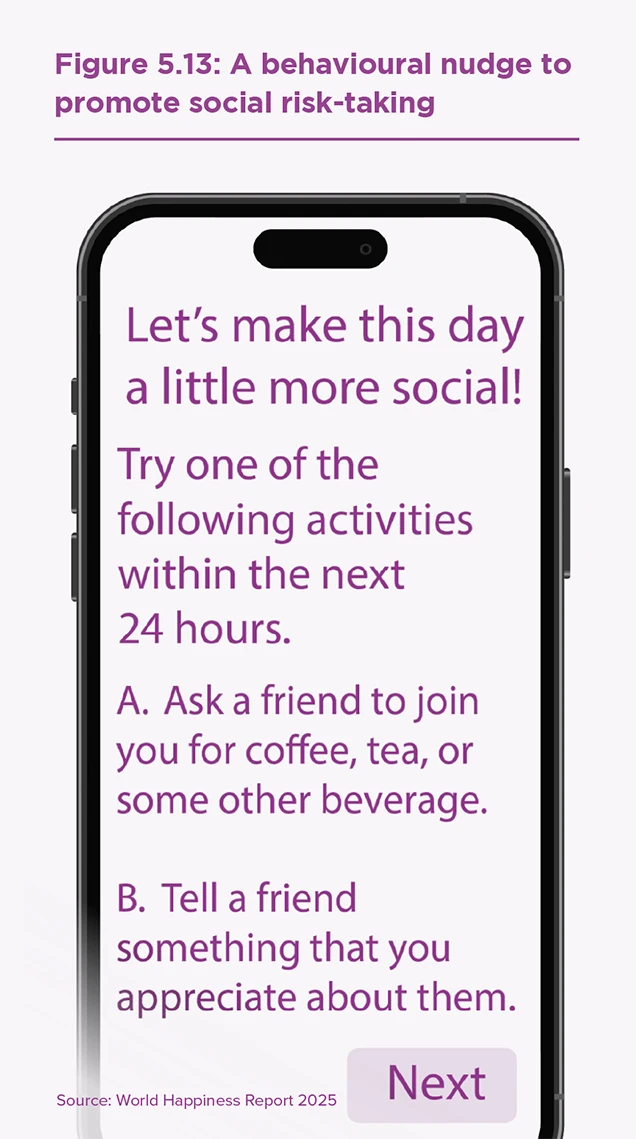

In the second experiment, we expanded the intervention by adding behavioural nudges delivered directly to students’ smartphones (Figure 5.13). These nudges encouraged students to engage in small, everyday acts of social risk-taking, such as complimenting a stranger or catching up with someone they hadn’t spoken to in a while. Once again, our intervention reduced the empathy perception gap. On average, participants in the control condition underestimated their peers’ empathy by 1.0 points on a 7-point scale. Those in the experimental condition also underestimated their peer’s empathy, but to a lesser degree (0.9 points), representing a 10% reduction.

Similarly, our intervention also increased acts of social risk behaviour. In the week following the intervention, experimental condition participants were 89% more likely to report engaging in social risk-taking compared to those in the control group. We also found that these effects were long-lasting. Two months after the intervention, students in the experimental group were still twice as likely to sign up for a social event in which they have an extended conversation with strangers compared to participants in the control group.

The intervention also strengthened students’ social networks. We assessed students’ friendship networks four months after the intervention and found that students in the experimental condition reported an average of 0.44 more close friends compared to those in the control group.

Together, results from these field experiments indicate that a community’s empathy can be a powerful, yet underutilised, resource for mental health and happiness. We provide initial evidence that interventions highlighting a community’s care and empathy, as well as behavioural nudges to encourage social risk-taking, can effectively shift people’s perceptions and behaviours, as well as expand social networks. These findings point to the importance of creating caring social environments and helping individuals to recognise the empathy that surrounds them.

Open questions and future directions

In previous sections, we described the robust relationships between different aspects of social connection and overall happiness in young adults. Next, we discuss some open questions and opportunities for future exploration.

Towards a multifaceted measure of social connection

Social connection is a multifaceted construct that encompasses the quantity, quality, and structure of an individual’s social network. Research so far has largely focused on the presence or absence of social ties, with an emphasis on social isolation and loneliness. This perspective overlooks the rich dimensions of social relationships. As the World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”,[67] social health is more than the absence of social deficit, and thus encompasses the fulfilling, supportive, and flourishing aspects of social connection.

A first step towards a more nuanced understanding of social connection is the creation and utilisation of a common measure that (1) encompasses different aspects of social connection, and (2) can be applied to diverse cultural contexts. A standardised, multifaceted measure of social connection can serve as a powerful tool to assess the state of social health globally, and offer valuable new insights into the intricate ways different aspects of social connection shape wellbeing.

Social connection is a multifaceted construct that encompasses the quantity, quality, and structure of an individual’s social network.

Furthermore, different factors of social connection could matter for the wellbeing of people that vary by cultural background, age group, and socio-economic status. For example, existing research finds that the quantity and quality of social interactions may be valued differently depending on one’s age. Individuals in their 20s may prefer quantity while those in their 30s may prefer quality.[68] Thus, a multifaceted measure of social connection assessing the global population can help researchers identify which aspects of social connection most strongly contribute to happiness across different groups.

An additional aspect that can be incorporated into existing measures of social connection is relationship diversity: the variety of relationship types within an individual’s social network. Recent research has highlighted a robust correlation between happiness and having a variety of relationships, such as family, close friends, coworkers, and acquaintances.[69] For example, a study of over 50,000 people reveals that interacting with a more diverse set of relationship types predicts higher wellbeing. This effect, comparable with other established contributors of wellbeing such as marital status, held after controlling for total time spent socialising as well as the diversity of activities that people engaged in.[70]

We are now seeing efforts to establish a global indicator of social connection. In 2022, Gallup, Meta, and a group of academic advisors collaborated on the State of Social Connections study, a first-of-its-kind, in-depth look at people’s social connections around the world. A second phase of the research, the State of Social Connections Gallup World Poll survey, expanded its global reach by running a select set of the State of Connections study questions on the Gallup World Poll, reaching over 140 countries and providing the ability to study overall life evaluations and the relative importance of the quantity, quality, and diversity of social connection.[71]

Prevention and intervention efforts to promote social connection

The trends of declining social connection among young adults, combined with the evidence on the associations between social connection and wellbeing, point to an urgent need to take action. Social connection generally occurs naturally among individuals and within communities. However, when it does not, intervention becomes necessary to reduce risk. We presented our own effort on intervention to enhance social connection among Stanford University students. Yet, much remains to be understood: which interventions work best, for whom, and under what circumstances? Below, we discuss a few directions for future research.

Technology-based interventions

Today’s young adults are the first generation to have grown up completely immersed in technology-based communications. Also called ‘digital natives’, young adults today have had access to the internet and digital devices from a very young age. Researchers are starting to learn more about the role of social networking and messaging apps in social connection and loneliness.

With the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models, research is needed to understand how best to use AI to enhance social connection and wellbeing. Preliminary research shows that AI-powered virtual companions — chatbots designed for conversation or emotional support — may offer short-term relief from loneliness. These tools simulate human interaction, providing immediate responses that mimic companionship. While their potential is exciting, robust research is essential to evaluate their long-term effectiveness and understand how best to integrate them into broader efforts to promote wellbeing.

Policy-based interventions

Social relationships are shaped, in large part, by systemic societal, economic, and technological factors. As such, there is growing interest in the role of policy-based interventions in fostering social connection and mitigating the growing trends in social isolation and loneliness.[72] These interventions aim to create structural changes that promote prosocial behaviours and relationships at scale, moving beyond individual efforts to address the broader contexts in which relationships emerge. An example of such efforts is the introduction of social and emotional learning (SEL) curriculum in schools. By embedding these practices into educational systems, SEL programs create an environment where healthier relationships can flourish, helping students develop critical tools for connection.[73]

Policy-based interventions hold great potential for fostering social connections. When we examine other public health challenges such as smoking cessation, societal-level efforts such as taxation and public health campaigns generally outperform individual-level approaches.[74] Policy-based interventions that address social isolation and loneliness are still sparse, so future progress will require rigorous, evidence-based research to carefully guide policy design and implementation.

Together, future work is needed to identify how interventions can effectively promote social connection, particularly through the promising avenues of technology and public policy. As we discussed above, social connection is not a one-dimensional, catch-all concept. It encompasses the quantity, quality, and the structure of social relationships that individuals are embedded in. As such, we need integrated, multi-level strategies that account for the interplay of these factors.[75]

Equally important is understanding when these interventions may have no effect or backfire. Well-intentioned efforts could inadvertently deepen isolation or exacerbate disparities. Future interventions that simultaneously address individual, community, and societal levels in a systematic way are likely to be the most effective at promoting social connection.

Conclusion

This chapter has examined the critical role of social connection in the happiness and wellbeing of young adults.

First, drawing from the Global Flourishing Study and the Gallup World Poll, we showed that social disconnection is prevalent and growing in young adults, and that both the quantity and quality of social connection robustly map onto subjective wellbeing.

Second, we reviewed classic and contemporary studies that underscore the importance of social relationships for human flourishing. Evidence in this area points to a robust link between social connection and wellbeing, both across individuals (happier people tend to report better social connection) and within the same individuals over time (people report greater happiness when more socially engaged). Building on these correlational findings, there is growing evidence that credibly demonstrates a significant causal effect of social connection on improved mental health. Individuals who are randomly assigned with social engagement tend to report lower stress when exposed to distressing stimuli, regulate their emotions better, and report more positive affect.

Third, we zoomed in on the Stanford Community Project; a large-scale, longitudinal project that focuses on one undergraduate student community. Data from this work have produced several discoveries that advance the basic science of community wellbeing and provide avenues through which to improve it: (1) friendships formed in the first few weeks of college significantly shape the long-term mental health trajectories of students; (2) both direct friendships and the broader ‘social microclimate’ can significantly contribute to wellbeing; (3) an ‘empathy perception gap’ — the tendency for young people to underestimate the empathy of their peers — leads to missed opportunities for connection; and (4) interventions that provide opportunities for students to learn about the empathy and care in their community can effectively shift empathy perceptions, encourage social risk-taking, and expand social networks. These findings point to novel, promising ways of bolstering connection and happiness among this age group.

In summary, this chapter highlights the multifaceted ways in which social connection influences the wellbeing of young adults. Our evidence points to practical opportunities to leverage social connection to enhance happiness. By targeting both individual relationships and the broader social environment, these strategies offer promising avenues for improving the happiness and wellbeing of young adults.

Interventions that provide opportunities for students to learn about the empathy and care in their community can effectively shift empathy perceptions, encourage social risk-taking, and expand social networks.

References

American College Health Association. (2023). American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2023. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Blanchflower, D. G., Bryson, A., & Xu, X. (2024). The Declining Mental Health of the Young and the Global Disappearance of the Hump Shape in Age in Unhappiness. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4794387

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2003). Friendship across the life span: Reciprocity in individual and relationship development. In Growing Together (pp. 159–182). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511499852.007

Bowman, N. A., & Park, J. J. (2015). Not all diversity interactions are created equal: Cross-racial interaction, close interracial friendship, and college student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 56(6), 601–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9365-z

Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M., & Luhmann, M. (2021). Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(8), 787–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000332

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216

Cai, D., Zhu, M., Lin, M., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. (2017). The bidirectional relationship between positive mental health and social rhythm in college students: A three-year longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01119

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165

Carstensen, L. L., Mikels, J. A., & Mather, M. (2006). Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation, and emotion. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (pp. 343–362). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012101264-9/50018-5

Choi, K. W., Lee, Y. H., Liu, Z., Fatori, D., Bauermeister, J. R., Luh, R. A., … Smoller, J. W. (2023). Social support and depression during a global crisis. Nature Mental Health, 1(6), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00078-0

Coan, J. A., Beckes, L., Gonzalez, M. Z., Maresh, E. L., Brown, C. L., & Hasselmo, K. (2017). Relationship status and perceived support in the social regulation of neural responses to threat. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(10), 1574–1583. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsx091

Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand: social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science, 17(12), 1032–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01832.x

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3901065

Collins, H. K., Hagerty, S. F., Quoidbach, J., Norton, M. I., & Brooks, A. W. (2022). Relational diversity in social portfolios predicts well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(43), e2120668119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2120668119

Courtney, A. L., Baltiansky, D., Fang, W. M., Roshanaei, M., Aybas, Y. C., Samuels, N. A., … Zaki, J. (2024). Social microclimates and well-being. Emotion , 24(3), 836–846. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001277

Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 13(9), 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3313

Diener, E., Kanazawa, S., Suh, E. M., & Oishi, S. (2015). Why people are in a generally good mood. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 19(3), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544467

Epley, N., & Schroeder, J. (2014). Mistakenly seeking solitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 143(5), 1980–1999. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037323

Figueira, C. P., Marques-Pinto, A., Pereira, C. R., & Roberto, M. S. (2017). How can academic context variables contribute to the personal well-being of higher education students? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20, E43. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2017.46

Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., Charles, S. T., & Umberson, D. J. (2020). Variety is the spice of late life: Social integration and daily activity. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(2), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz007

Fry, R., Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. ’vera. (2020, September 4). A majority of young adults in the U.S. live with their parents for the first time since the Great Depression. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from Pew Research Center website: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/09/04/a-majority-of-young-adults-in-the-u-s-live-with-their-parents-for-the-first-time-since-the-great-depression/

Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

Granovetter, M. (1992). Economic institutions as social constructions: A framework for analysis. Acta Sociologica, 35(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939203500101

Gunaydin, G., Oztekin, H., Karabulut, D. H., & Salman-Engin, S. (2021). Minimal social interactions with strangers predict greater subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1839–1853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00298-6

Harris, K., English, T., Harms, P. D., Gross, J. J., & Jackson, J. J. (2017). Why are extraverts more satisfied? Personality, social experiences, and subjective well–being in college: Extraverts and social experience. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2101

Helliwell, Huang, H., Shiplett, H., Wang, S., & World Happiness Report. (2024). Happiness of the younger, the older, and those in between. University of Oxford. https://doi.org/10.18724/WHR-F1P2-QJ33

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2024). Social connection as a critical factor for mental and physical health: evidence, trends, challenges, and future implications. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 23(3), 312–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21224

Hu, S., Cai, D., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. (2020). Relationship between social support and positive mental health: A three-wave longitudinal study on college students. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 41(10), 6712–6721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01175-4

Jacques-Hamilton, R., Sun, J., & Smillie, L. D. (2019). Costs and benefits of acting extraverted: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 148(9), 1538–1556. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000516

Johnson, B. R., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2022). The Global Flourishing Study: A New Era for the Study of Well-Being. International Bulletin of Mission Research, 46(2), 272–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969393211068096

Kardas, M., Schroeder, J., & O’Brien, E. (2022). Keep talking: (Mis)understanding the hedonic trajectory of conversation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123(4), 717–740. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000379

Krakauer, J. (1996). Into the Wild. Anchor Books.

LaFreniere, J. R. (2024). Defining and discussing independence in emerging adult college students. Journal of Adult Development, 31(4), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09472-5

Langston, C. A. (1994). Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1112–1125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1112

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

Lemmens, V., Oenema, A., Knut, I. K., & Brug, J. (2008). Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: a systematic review of reviews. European Journal of Cancer Prevention: The Official Journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP), 17(6), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48

Lepore, S. J., Allen, K. A., & Evans, G. W. (1993). Social support lowers cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(6), 518–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199311000-00007

Margraf, J., Zhang, X. C., Lavallee, K. L., & Schneider, S. (2020). Longitudinal prediction of positive and negative mental health in Germany, Russia, and China. PloS One, 15(6), e0234997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234997

Marsden, P. V. (1993). The reliability of network density and composition measures. Social Networks, 15(4), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(93)90014-c

Master, S. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Taylor, S. E., Naliboff, B. D., Shirinyan, D., & Lieberman, M. D. (2009). A picture’s worth: partner photographs reduce experimentally induced pain. Psychological Science, 20(11), 1316–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02444.x

Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2011). Wellbeing and resilience in young people and the role of positive relationships. In Positive Relationships (pp. 17–33). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2147-0_2

Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S. surgeon general’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37792968/

Pei, R., Courtney, A. L., Ferguson, I., Brennan, C., & Zaki, J. (2023). A neural signature of social support mitigates negative emotion. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 17293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43273-w

Pei, R., Grayson, S. J., Appel, R. E., Bouwer, A., Huang, E., Jackson, M. O., … Zaki, J. (in prep). Bridging the Gap: Enhancing Empathy Perceptions Fosters Social Connection.

Pei, R., Kranzler, E., Suleiman, A. B., & Falk, E. B. (2019). Promoting adolescent health: Insights from developmental and communication neuroscience. Behavioural Public Policy, 3(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.30

Perry, B. L., Smith, N. C., Coleman, M. E., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2024). Social networks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and emerging adults’ mental health: Resiliency through social bonding and cohesion. American Journal of Public Health, 114(S3), S258–S267. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307426

Peters, B. J., Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2018). Making the good even better: A review and theoretical model of interpersonal capitalization. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(7), e12407. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12407

Quoidbach, J., Taquet, M., Desseilles, M., de Montjoye, Y.-A., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Happiness and social behavior. Psychological Science, 30(8), 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619849666

Ramos, M. R., Li, D., Bennett, M. R., Mogra, U., Massey, D. S., & Hewstone, M. (2024). Variety is the spice of life: Diverse social networks are associated with social cohesion and well-being. Psychological Science, 35(6), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976241243370

Reis, H. T., Smith, S. M., Carmichael, C. L., Caprariello, P. A., Tsai, F.-F., Rodrigues, A., & Maniaci, M. R. (2010). Are you happy for me? How sharing positive events with others provides personal and interpersonal benefits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018344

Rhoads, S. A., & Marsh, A. A. (2023). Doing Good and Feeling Good: Relationships Between Altruism and Well-being for Altruists, Beneficiaries, and Observers. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/doing-good-and-feeling-good-relationships-between-altruism-and-well-being-for-altruists-beneficiaries-and-observers/

Rimé, B. (2007). The social sharing of emotion as an interface between individual and collective processes in the construction of emotional climates. The Journal of Social Issues, 63(2), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00510.x

Rohrer, J. M., Richter, D., Brümmer, M., Wagner, G. G., & Schmukle, S. C. (2018). Successfully striving for happiness: Socially engaged pursuits predict increases in life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 29(8), 1291–1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618761660

Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Social interactions and well-being: The surprising power of weak ties. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(7), 910–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214529799

Schroeder, J., Lyons, D., & Epley, N. (2022). Hello, stranger? Pleasant conversations are preceded by concerns about starting one. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 151(5), 1141–1153. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001118

Sompolska-Rzechuła, A., & Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. (2022). Generation of young adults living with their parents in European Union countries. Sustainability, 14(7), 4272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074272

Srivastava, S., Angelo, K. M., & Vallereux, S. R. (2008). Extraversion and positive affect: A day reconstruction study of person–environment transactions. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1613–1618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.05.002

Stein, E. R., & Smith, B. W. (2015). Social support attenuates the harmful effects of stress in healthy adult women. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.038

Stokes, J. P. (1985). The relation of social network and individual difference variables to loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 981–990. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.981

Sun, J., Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2020). Is well-being associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1478–1496. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000272

Boneva, B., Quinn, A., Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., & Shklovski, I. (2006). Teenage communication in the instant messaging era. In R. Kraut, M. Brynin, & S. Kiesler (Eds.), Computers, phones, and the Internet: Domesticating information technology (pp. 201–218). Oxford University Press.

Thayer, R. E., Newman, J. R., & McClain, T. M. (1994). Self-regulation of mood: Strategies for changing a bad mood, raising energy, and reducing tension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 910–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.910

Uchino, B. N., & Garvey, T. S. (1997). The availability of social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025583012283

Vaillant, G. E. (2008). Aging well: Surprising guideposts to a happier life from the landmark study of adult development. Little, Brown.

Velten, J., Bieda, A., Scholten, S., Wannemüller, A., & Margraf, J. (2018). Lifestyle choices and mental health: a longitudinal survey with German and Chinese students. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 632. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5526-2

Waldinger, R., & Schulz, M. (2023). The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. Simon and Schuster.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., Weber, K., Assenheimer, J. S., Strauss, M. E., & McCormick, R. A. (1995). Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.104.1.15

Westaby, J. D., Pfaff, D. L., & Redding, N. (2014). Psychology and social networks: a dynamic network theory perspective. The American Psychologist, 69(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036106

Wickramaratne, P. J., Yangchen, T., Lepow, L., Patra, B. G., Glicksburg, B., Talati, A., … Weissman, M. M. (2022). Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PloS One, 17(10), e0275004. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275004

Williams, W. C., Morelli, S. A., Ong, D. C., & Zaki, J. (2018). Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(2), 224–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000132

World Health Organization (2006). A state of complete physical mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Constitution of the World Health Organization Basic Documents, 45, 1–20.

Ye, J., Yeung, D. Y., Liu, E. S. C., & Rochelle, T. L. (2019). Sequential mediating effects of provided and received social support on trait emotional intelligence and subjective happiness: A longitudinal examination in Hong Kong Chinese university students. International Journal of Psychology, 54(4), 478–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12484

Zhao, X., & Epley, N. (2021a). Insufficiently complimentary?: Underestimating the positive impact of compliments creates a barrier to expressing them. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000277

Zhao, X., & Epley, N. (2021b). Kind words do not become tired words: Undervaluing the positive impact of frequent compliments. Self and Identity: The Journal of the International Society for Self and Identity, 20(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2020.1761438

Zhao, X., & Epley, N. (2022). Surprisingly Happy to Have Helped: Underestimating Prosociality Creates a Misplaced Barrier to Asking for Help. Psychological Science, 33(10), 1708–1731. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221097615

Zou, X., Ingram, P., & Higgins, E. T. (2015). Social networks and life satisfaction: The interplay of network density and regulatory focus. Motivation and Emotion, 39(5), 693–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9490-1

Endnotes

Blanchflower et al. (2024). ↩︎

Helliwell et al. (2024). ↩︎

Cohen and Wills (1985); Wickramaratne et al. (2022); Holt-Lunstad (2024). ↩︎

Choi et al. (2023); Coan et al. (2006). ↩︎

Stein and Smith (2015); Williams et al. (2018). ↩︎

Buecker et al. (2021). ↩︎

American College Health Association (2023). ↩︎

Crone and Dahl (2012); Pei et al. (2019). ↩︎

Sompolska-Rzechuła and Kurdyś-Kujawska (2022). ↩︎

Fry et al. (2020). ↩︎

Larson (2000). ↩︎

Arnett (2000). ↩︎

LaFreniere (2024). ↩︎

Boneva et al. (2006). ↩︎

Noble and McGrath (2011). ↩︎

Johnson and VanderWeele (2022). ↩︎

Blieszner and Roberto (2003). ↩︎

Carstensen et al. (2006). ↩︎

Helliwell et al. (2024). ↩︎

Buecker et al. (2021). ↩︎

b = 0.92, 95% CI = [0.85, 0.99], p < 0.001. ↩︎

b = 0.29, 95% CI = [0.28, 0.30], p < 0.001. ↩︎

Quantity: standardized b = 0.77, 95% CI = [0.70 - 0.85], p < 0.01; Quality: standardized b = 0.84, 95% CI = [0.82-0.87], p < 0.01. ↩︎

We focus on subjective wellbeing in this chapter. Evidence also points to social connection as a critical factor for physical health. Interested readers can see Holt-Lunstad (2024) for a recent review on this topic. ↩︎

Waldinger and Schulz (2023). ↩︎

Vaillant (2008). ↩︎

Cacioppo et al. (2010). ↩︎

Rohrer et al. (2018). ↩︎

Harris et al. (2017). ↩︎

Cai et al. (2017); Figueira et al. (2017);Hu et al. (2020); Margraf et al. (2020); Velten et al. (2018); Ye et al. (2019) ↩︎

Srivastava et al. (2008). ↩︎

Sun et al. (2020). ↩︎

Quoidbach et al. (2019); Rimé (2007). ↩︎

Diener et al. (2015); Watson et al. (1995). ↩︎

Thayer et al. (1994). ↩︎

Quoidbach et al. (2019). ↩︎

Rhoads and Marsh (2023). ↩︎

Choi et al. (2023); Coan et al. (2006); Cohen and Wills (1985). ↩︎

Lepore, Allen, & Evans (1993); Uchino and Garvey (1997). ↩︎

Coan et al. (2017). ↩︎

Master et al. (2009); Pei et al. (2023). ↩︎

Jacques-Hamilton et al. (2019); Schroeder et al. (2022) ↩︎